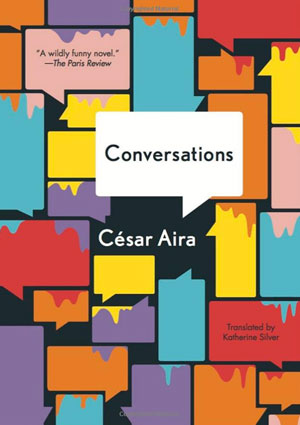

CONVERSATIONS

by César Aira

translated by Katherine Silver

New Directions, 88 pages

reviewed by Ana Schwartz

The Little Estancias

Domestic Tourism

What’s the name for the genre of writing about a house? House tourism exists, but what about house-writing? It would be a good word to have on hand when reading Argentina: The Great Estancias, because whatever that genre is, this book is the exemplar. An estancia is a large estate originating in colonial settlement of Latin America and supported by agricultural industry, usually livestock. Despite regional variation across Latin America (and the use of different names, like hacienda), they generally consist of a large central house and several smaller edifices across acres upon thousands of acres of land. True to the title, the nation of Argentina is the primary subject of this book. Its history and culture are beautifully recorded in the photographs by Tomás de Elia and Cristina Cassinelli de Corral, alongside the descriptive text by César Aira.

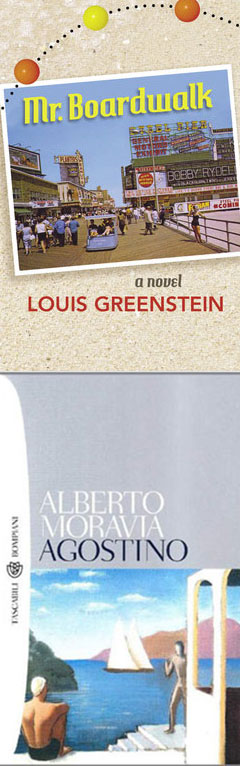

César Aira

Yes, that César Aira. The same Aira whose Spanish language oeuvre—over 60 novels, plus essays and a few monographs—has been, since 2006, slowly appearing in English, thanks to the editors at New Directions Paperbacks. The latest, Conversations, in the English translation by Katherine Silver, was published earlier this year. At 80-120 pages, most of these books are shorter than the conventional novel. Their smallness practically invites smuggling and stowing them into the pockets of coats or backpacks or purses. They want to be shared, reread, and picked up again in new places. On the other hand, Argentina: The Great Estancias is a large, clothbound coffee table book, in the style of a museum catalogue. You might need access to a university library to look through it. If you wanted to buy a proper copy and show it off, you’d probably want a nice coffee table—and a nice living room. But once you open the book, you’ll want to get back up again, pack your bags and spend an entire upside-down year in the Southern Hemisphere, visiting each of the beautiful estates: from La Calavera, in the northern province of Salta; to Harberton in Tierra del Fuego, which boasts gated threshold made out of a whale’s jawbone.

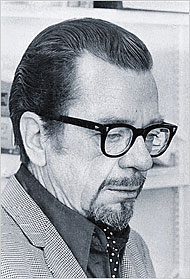

Katherine Silver

But what would you do when you got there? Just look around? What greater experience than visual delight might you reasonably expect? In one of his earlier novels, Aira describes this underlying strangeness of travel with directness and clarity. “What would they go there to do?” he asks. Regarding tourists considering the pampas, he adds, “I don’t think traveling is worth the trouble if you don’t bring your life along with you.” Likewise, even if the images of Argentinean culture inspire envy, Aira’s historically conscious text is more ambivalent. He returns frequently to the less-than celebratory origins of these estates: most are the ancestral homes of colonial European families that settled in Argentina during the past four centuries. Some, like Santa Catalina, date back to the late sixteenth century. Others, like the main house at Huetel, were built as recently as 1905. Aira doesn’t dwell for very long on these statistical details—he moves briskly from room to room, episode to historical episode, and he is forthright about what’s represented by the windows with iron grillwork at Rincón de López, which testify to the many wars with local Indians. The past was savage, even despite the beauty of de Elia and de Corral’s photographs. Maybe it is best to stay at home with the novels.

Global Literature

One could do worse. The novels are a thrilling, if often unbelievably weird, introduction to Argentinean history and culture, as well as people and places around the world. Settings and also plots vary rather fantastically. Many of the novels take place in contemporary Argentina, or the pampas of the southern cone. Some transpire elsewhere, in other historical periods—a conference in Mexico City, for example, or the bustling Panama City of the nineteenth century. The works show a commitment to pan-Latinidad, but just as frequently offers a wider international perspective: that of a German painter, for example, an English naturalist, or a Hollywood actor pretending to pretend to be a Ukrainian—!—goatherd. The decorative coffee table book describes the land through its history of territorial settlement, but the novels, which are more interested in human mobility, in the speed and transience brought by globalization.

Each novel cares about the past, but the trick is figuring out how to read the manifestations of history on the terms each novel sets for itself. On this, Varamo is exemplary. In this novel, translated by Chris Andrews in 2012, the literary-critic narrator speculates on how the great Panamanian national epic came into being. The made-up long poem, The Song of the Virgin Boy, was written in 1923 by an otherwise unremarkable, unliterary, yet honest and earnest government employee named Varamo. The narrator begins with an admission of perplexity: none of his familiar methods of literary criticism explain this text. The best account he can give is through describing the diverse population of early twentieth century Panama: The effect of the canal on the city of Colón is never explicitly described during the course of the novel, but implicitly omnipresent in the scenes of trade and transportation of commodities. Varamo has recently left his job after unintentionally getting involved in a counterfeiting incident. He decides to write a short, sort of practical book: a taxidermy manual. As he perambulates Panama City he solicits writing advice from his friends and neighbors, characters from around the world. It’s good advice, too: they tell him that “writing was very easy and could be done very quickly…write out the notes one after another, with some commentary in between. Try not to tidy them up too much; immediacy is the key to a good style.” Maybe the advice is too effective: instead of a how-to guide, the miracle of Panamanian literature is born that night.

Human mobility, and the creativity it variously engenders, recurs as a motif throughout these books: The Miracle Cures of Dr. Aira shows the doctor on the run from a mysterious villain. Much of The Literary Conference takes place en route to a conference in Mexico. Shantytown focuses on a group of homeless families, migrant laborers, who are constantly on the move; even the doors of their temporary houses sometimes move too, unaccountably. Consider the technique of Johann Moritz Rugendas, the real-life landscape painter of An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter and a disciple of the German explorer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. His travels to Argentina take him through the Chilean Andes; its sublime peaks and the contrast with the equally impressive Argentinean pampas elicit some fine meditations on method: “Everything was human,” Rugendas observes, “the farthest wilderness was steeped with sociability.” But the calm projection of self into nature isn’t where genius originates. It also derives from the outside world’s violent attack on the human: in a hurried rush across the pampas during a thunderstorm, lightning strikes Rugendas and hideously transmogrifies him. This leads to his development of a style that Aira observes will eventually be called surrealism. More vitally, for Rugendas, it is a “physiognomy of nature.” Examples of Rugendas’ sketches, by the way, can be found at the Los Alamos estancia, in the Mendoza province.

Conversational Reading

Conversations is his most geopolitical work thus far. It is a short book that spans several continents; the real and the fabricated and the forgotten; the personal and the public. Katherine Silver, the translator, also brought English language readers The Miracle Cures of Dr. Aira and The Literary Conference. She has translated fiction by fellow Argentinean Ernesto Mallo, the Mexican writer Daniel Sada, and Salvadorean writer Horacio Castellanos Moya, among many others.

The plot of Conversations seems pretty flimsy at first: an unnamed narrator lies in bed one night, and, as is his custom, reviews his day’s conversations. For him, the mnemonic act is also a creative. It has its own rules, which, executed successfully, yield a sense of productive satisfaction. The particular conversation of the novel had taken place on the phone between the narrator and his dear friend, also unnamed. They have both watched a made-for-TV movie, a romance. The narrator was troubled by an illogical detail—an expensive watch on the wrist of an otherwise very poor goatherd in the mountains of Ukraine. The two men review their memory of the film. The narrator speculates about the visibility of the watch. He turns first to the vast complexities of the modern-day film industry. His friend interprets the watch by showing how the first explanation was actually a part of the plot itself: didn’t he see that it was a movie about the making of a movie?

Generally, in the earlier novels, Aira is interested in what generates and sustains creativity, often in the form of writing. This is Aira’s first translated novel to imagine how a creative artifact is read. Here, Aira elevates the practice of reading to a form of creativity. For that work, friendship is essential, because any individual’s experience of a text—the observable details, and the memorable details—aren’t available to any one person, even a really smart, really observant loner who spends most of his time thinking. The friendship also gives a wider experience of reading methods. Like the narrator of Varamo, this narrator is a good historical materialist, who attends to the means of production; but his friend corrects against his narrow focus by showing its limitations, as well as the political implications of his myopia. Like the 2012 Ben Affleck film Argo about the 1979 Iran hostage crisis, the production within the plot masked an international covert operation, but it’s not so clearly admirable a mission as the extraction of captive hostages.

So if it is a novel about how to read, then it is also a novel about how to be friends, and how to talk about friendship. It’s hard to overstress this element of the book, since Aira himself overdoes it, gleefully. Earnest moralizing about the value of friendship? Lessons on the importance of being a good listener? How repulsive! When the narrator makes these statements, though, he’s aware that his self-importance seems extravagant. Irony and overstatement work in Aira’s favor by creating a bit of breathing room for the narrator to flesh out the qualities of his relationship as well as specific examples of how much and why he needs his friends “to tightly pack in the attractions by filling in the dead times that inevitably exist in a story told by a single person.” The entire novel unfolds during a lonely and sleepless night that is characteristic for this narrator; those who’ve ever experienced a time of insomnia can attest to the pervasive feeling of morbidity. The narrator claims to allow his friendships to take hold in his heart, as if lonesome nighttime brooding were a choice. Coincidentally, this is the only novel so far that does not feature significant travel or movement for the main character.

The method of reading enacted here is instructive to a global readership. Through relationships like this, Aira suggests a perspective on the world, not only a way to read his complex little fictions. In this story that perspective is especially evident: the main plot is practically nonexistent, but the plots-within-plots are so geopolitically attuned, requiring the keen viewers of the novel to know a great deal about international politics. So far Aira’s fiction has kept the explicit geopolitical conversations on a quieter volume, and subordinated to formal playfulness. In The Hare (reviewed in these pages a year ago), for example, the conversations set the groundwork for eventual narrative discovery. Clarke, an English naturalist of the nineteenth century, comes to Argentina to search for the legendary Legibrerian Hare. This novel is the longest of Aira’s translated fiction and it reads like an English novel—at the end, the plot’s many important characters realize that they are all, mostly, related. The final twist mimics and mocks its precedent in the nineteenth-century English family novel. But the ongoing conversation between Clarke and Carlos, and their meditations on how storytelling can bring people together, but also divide them. This is the real sustaining energy of the text.

The Morphological Cures of Prof. Aira

The books themselves often seem like the author’s friendly interlocutor. Some version of César or Aira appears in many of the fictions, often with a curious mutation. In the Miracle Cures of Dr. Aira, for instance, a Dr. Aira peddles a mysterious, quasi-religious cure for a likewise mysterious ailment. In How I Became a Nun, a child César does not become a nun, but rather switches genders. In The Seamstress and the Wind, a reflective and erudite novelist named César Aira sits in a Paris café and writes: but the memory he shares about his life is, like the details of those other novels, equally surreal.

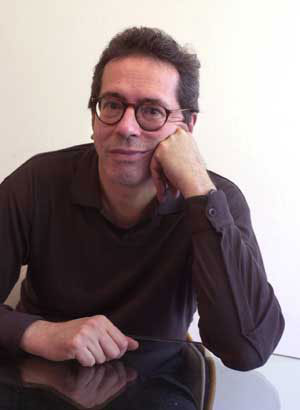

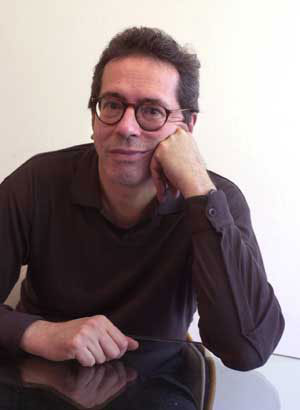

Unlike the protagonist of The Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter, though, César Aira is, on the outside, at least, no disfigured monster. He looks like a laid back, still energetic middle-aged guy, with a literature professor’s skeptical earnestness—or maybe that last is just the clunky spectacles. This probably isn’t too far off the mark. Aira was born in 1956 in Coronel Pringles, in the province of Buenos Aires, but well beyond the capital, where he moved at eighteen. He has lived most of his life in Argentina, although earlier in his career, he made a living off of translating genre fiction. In addition to a coffee table book and several novels, he writes literary essays and he lectures on English, Spanish, and French literature. Through the essays and lectures, he’s defined and named the organizing principle of his style as like a “continuo,” a “continuum.” Elaborating on the formal qualities, he calls it a “fuga hacia adelante,” a “flight forward,” which also describes his interest in territory and the nature of global communities.

His commitment to forward flight aligns him, at least formally, with the Oulipo, a mostly French avant-garde movement of the late twentieth century, still practiced by writers like Jacques Roubaud. In his Great Fire of London trilogy, Roubaud explains that he just wrote sentence after sentence, branching off when necessary, but never erasing or going backward. Aira also acknowledges a debt to surrealism, or its putatively Latin American variant, magical realism. The hero of The Literary Conference, for example, is traveling to Mexico to attend a meeting where Carlos Fuentes will be the honored guest. But he’s not there to celebrate; he is there to steal. Alas, the best laid plans! The protagonist’s bad science, and the author’s slightly better science fiction ends up cloning a giant blue worm out of Fuentes’ necktie!

Thematically, though, Aira’s work shows subtle, but pervasive affinity with his contemporaries of the Crack Generation (where there was Macondo there is now McOndo); its most famous star, the Chilean expatriate Roberto Bolaño, wrote the introduction to The Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter, announcing Aira to be “one of the three or four best writers working in Spanish today.” Bolaño’s stamp endures on the cover of almost every consequent translation. In the short essay, Bolaño quietly praises Aira’s attention to the poor when he calls him a nun in the “Discalced Carmelites of the Word.” Likening him to the mendicants who beg for their food, Bolaño describes both Aira’s commitment to writing as well as to tenderness and humility.

These qualities are most powerfully communicated in 2011’s Shantytown, a novel whose realism relative to the early novels is motivated by a belief stated clearly and powerfully by the smallest of characters, Adela, the tiny maid of the protagonists’ household: “In the old days,” she observes, “there were poor people and rich people because there was a world made up of the poor and the rich. Now that world has disappeared and the poor have been left without a world.” One of the difficulties in representing a world for the poor in the twenty-first century is that they are required to live such a transient lives. The very articulate, personable protagonists represent one experience of transience, a more privileged experience, certainly, but they also help make visible the existence of those whose world easily disappears.

But what effect can any one reader or spectator have on that world? Aira’s answer is complex. In the same novel, he makes an observation that nicely sums up individual experience from the perspective of historical determinism: “If you do something on an impulse, or because you feel like it, or just like that, without knowing why, it’s still you doing it, and you have a history that has led to that particular point in your life, so it’s not really a thoughtless act, far from it; you couldn’t given it any more though: you’ve been thinking it out ever since you were born.”

For Maxi, young middle-class protagonist of Shantytown, this means that the dissatisfactions of home life urge him towards reflexively, if not always reflectively, cultivating friendships with the oppressed laboring class. Their insight on the inequality in the world shows him his relative unimportance as an individual and maybe even diminishes his anxiety about personal vocation and fulfillment. He helps them, too; not much, but they appreciate it. Mostly they appreciate his ongoing and unexplained commitment. Aira does not turn earnest care for the poor into another self-congratulatory property of the well-off; he avoids describing the interior of the shantytowns. Unlike the empty and well-storied estancias, he will not enter the homes of these workers, although he will show their ongoing labor and struggle.

The Grandes Estancias

But if human actions, even the most spontaneous, are products of history, what about literary trends? What factors account for Aira’s recent popularity? Why are these little books so marketable? It doesn’t hurt to look at the obvious. As with the Fuentes fan and his Macuto Line, following the obvious yields valuable insight: Aira’s books are perfect for traveling. Not only because they’re portable, although that’s nice too. They’re swiftly-paced and provocative. They yield more on second readings, often describing in the strangeness of liminal, nomadic experience thoughtful, provocative riffs that are frequently more pleasurable than the storylines. If, for example, you finished How I Became a Nun on the first leg of a coast-to-coast flight, you might still be able to think about what in the world just happened; then you might snack on small pretzels before dozing off, and then read it again to make sure you didn’t dream it up. Depending on your reading speed, you might even watch a made-for-TV movie before descending. Your carry-on would be barely any heavier and if you wanted someone to talk about it with, its brevity would be one great recommendation.

Ease of mobility is such an important feature of contemporary life that it is easy to take it for granted. One thing The Great Estancias shows is the relatively novel quality of this. As soon as the Europeans arrived from across the oceans and sufficiently proved their intentions to stay, often by means of great violence and forced labor, they built enormous estates. The impressively solid, stable quality of those estates, at least for now, contrasts with the stony ruins of those who had lived there before. The Europeans wanted to not move again, but their desires led to a great deal of suffering and exploitation. And so in the novels, Aira focuses on the labor of building, settlement, and home-making. Those who have spent a lot of time transit, or those who move around frequently from city to city, even in the most privileged conditions, can relate to some degree to the estrangement from a solid home experience by, for example, the characters of Ghosts. There, Chilean laborers squat in the proleptically haunted condominium complex that they are also building. When tenants move in and they move on, they too will fade, spectrally, from memory. Although few of Aira’s English language readers will experience those circumstances, the longing for home has a powerful emotional resonance. Toasting to their old home at the New Year, they sigh: “Chilean wines are so dry! They said, sipping it, with a touch of nostalgia, which they reined in so as not to spoil the evening. They’re so dry, so dry! Paradoxically, that dryness filled their eyes with tears.”

Despite their size, the novels house many people and grand ideas. Like the estancias, each has a character or personality of its own; each tells a unique story about Argentina and the larger world. The translator Katherine Silver, following the metaphor of inhabitation, attributes Aira’s popularity to their noncommittal quality. Even if they’re frustrating, she observes, “you’re not going to have to stay there with him.” Perhaps she has in mind the new translation of Leopoldo Marechal’s 1948 classic, Adan Buenosayres, the Argentinean modernist epic, and a very long book. Unlike the Panamanian epic of Varamo, Song of the Virgin Boy, it is a novel, and has been dubbed the Ulysses of Buenos Aires. What would the Aira estancia look like? If there were to be a great epic of the Americas in the globalized twenty-first century—for those who are skeptical of Bolaño’s 2666’s claim to that title—maybe Aira will sit down one day and unexpectedly write it. It will probably take place in one large house. But more likely, he will continue writing short, strange sojourns; books that migrate into the mind and stay there, or that visit for one long party. One could hardly ask for a more fascinating get-together than the celebration Aira describes at Miraflores estancia in the Buenos Aires province: “In 1993, the Ramos Mejía family held a reunion lunch where they gathered together fifteen hundred of the forty-five hundred descendants of the couple that had traveled across the pampas in a wagon caravan to found Miraflores among the Indians.”

Ana Schwartz is a doctoral candidate in English literature at the University of Pennsylvania and teaches high school English in the suburbs of Philadelphia. She is working on a translation of Herralde Prize-winning author Alvaro Enrigue’s first novel.

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Book Reviews.

THE GUILD OF SAINT COOPER

THE GUILD OF SAINT COOPER

A recent graduate from Purchase College, Justin Goodman is working to establish a career and develop knowledge of the literary scene. His writing has been published in Submissions Magazine and Italics Mine.

A recent graduate from Purchase College, Justin Goodman is working to establish a career and develop knowledge of the literary scene. His writing has been published in Submissions Magazine and Italics Mine.

OUR ENDLESS NUMBERED DAYS

OUR ENDLESS NUMBERED DAYS

Elizabeth Mosier is a novelist and essayist. Her reviews have appeared most recently in The Philadelphia Inquirer and Cleaver. Read more at

Elizabeth Mosier is a novelist and essayist. Her reviews have appeared most recently in The Philadelphia Inquirer and Cleaver. Read more at  PREPARATION FOR THE NEXT LIFE

PREPARATION FOR THE NEXT LIFE

THE BOATMAKER

THE BOATMAKER

Claire Rudy Foster lives in Portland, Oregon. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing. Her critically recognized short fiction has appeared in various respected journals and she has been honored by several small presses, including a nomination for the Pushcart Prize. She is currently at work on a novel.

Claire Rudy Foster lives in Portland, Oregon. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing. Her critically recognized short fiction has appeared in various respected journals and she has been honored by several small presses, including a nomination for the Pushcart Prize. She is currently at work on a novel. FOURTEEN STORIES, NONE OF THEM ARE YOURS

FOURTEEN STORIES, NONE OF THEM ARE YOURS

Jacob White is the author of the story collection Being Dead in South Carolina (Leapfrog, 2013). His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Salt Hill, Shenandoah, Denver Quarterly, The Georgia Review, Hobart Online, and elsewhere. He currently teaches writing at Ithaca College in Ithaca, New York.

Jacob White is the author of the story collection Being Dead in South Carolina (Leapfrog, 2013). His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Salt Hill, Shenandoah, Denver Quarterly, The Georgia Review, Hobart Online, and elsewhere. He currently teaches writing at Ithaca College in Ithaca, New York. LEAVETAKING

LEAVETAKING

TIME PRESENT AND TIME PAST

TIME PRESENT AND TIME PAST

Annika Neklason grew up in Santa Cruz, California. She currently resides in Philadelphia, where she is pursuing a degree in English at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the Bassini Writing Apprentice for Cleaver Magazine.

Annika Neklason grew up in Santa Cruz, California. She currently resides in Philadelphia, where she is pursuing a degree in English at the University of Pennsylvania. She is the Bassini Writing Apprentice for Cleaver Magazine. WE’LL GO TO CONEY ISLAND

WE’LL GO TO CONEY ISLAND

THE CAPTAIN’S DAUGHTER

THE CAPTAIN’S DAUGHTER

Derek M. Brown is an English major at Columbia University. He is also a singer/songwriter and performs regularly throughout New York City.

Derek M. Brown is an English major at Columbia University. He is also a singer/songwriter and performs regularly throughout New York City.  BOMBYONDER

BOMBYONDER

Wyoming/Colorado native Brent Terry has published poems, stories, essays and reviews in many magazines and journals. He is the author of two collections of poetry: the chapbook yesnomaybe (Main Street Rag, 2002) and the full-length Wicked, Excellently (Custom Words, 2007). Terry received an MFA from Bennington in 2001. In 2111 he was awarded a fellowship from the Connecticut Arts and Tourism Board. A former neighborhood poet laureate in Minneapolis, Terry now lives in Willimantic, CT, where he scandalizes the local deer population with the brazen skimpiness of his running attire and teaches at Eastern Connecticut State University, but still yearns to rescue a border collie and light out for the Rockies.

Wyoming/Colorado native Brent Terry has published poems, stories, essays and reviews in many magazines and journals. He is the author of two collections of poetry: the chapbook yesnomaybe (Main Street Rag, 2002) and the full-length Wicked, Excellently (Custom Words, 2007). Terry received an MFA from Bennington in 2001. In 2111 he was awarded a fellowship from the Connecticut Arts and Tourism Board. A former neighborhood poet laureate in Minneapolis, Terry now lives in Willimantic, CT, where he scandalizes the local deer population with the brazen skimpiness of his running attire and teaches at Eastern Connecticut State University, but still yearns to rescue a border collie and light out for the Rockies. LEARNING CYRILLIC

LEARNING CYRILLIC

Jon Busch lives in Northwest Philadelphia. He spends his days working as the co-owner and content manager for Apollo Content. In the evenings, he can be found writing stories or playing music at open mic nights around the city. His fiction, book reviews, and interviews have been published or are forthcoming at Crack the Spine, Cleaver, Bird’s Thumb, Foliate Oak, Philadelphia Stories, Piker Press, and Baby Teeth Magazine. His work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Jon Busch lives in Northwest Philadelphia. He spends his days working as the co-owner and content manager for Apollo Content. In the evenings, he can be found writing stories or playing music at open mic nights around the city. His fiction, book reviews, and interviews have been published or are forthcoming at Crack the Spine, Cleaver, Bird’s Thumb, Foliate Oak, Philadelphia Stories, Piker Press, and Baby Teeth Magazine. His work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. THE SCAPEGOAT

THE SCAPEGOAT

Cleaver reviews editor

Cleaver reviews editor  THE DOOR

THE DOOR

HOW YOU WERE BORN

HOW YOU WERE BORN

Michelle Fost is a writer living in Toronto. Her fiction has appeared in The Painted Bride Quarterly and her book reviews have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and The Boston Phoenix Literary Section.

Michelle Fost is a writer living in Toronto. Her fiction has appeared in The Painted Bride Quarterly and her book reviews have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and The Boston Phoenix Literary Section. YOU’LL ENJOY IT WHEN YOU GET THERE

YOU’LL ENJOY IT WHEN YOU GET THERE

EVERLASTING LANE

EVERLASTING LANE

THE OPPOSITE OF LONELINESS

THE OPPOSITE OF LONELINESS

THE USE OF MAN

THE USE OF MAN

10:04

10:04

WORKING STIFFS

WORKING STIFFS

BRIEF EULOGIES AT ROADSIDE SHRINES

BRIEF EULOGIES AT ROADSIDE SHRINES

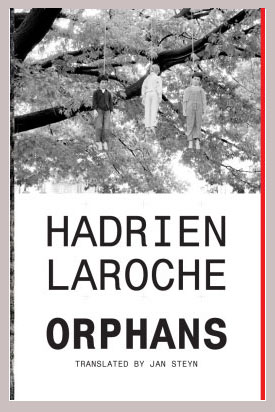

ORPHANS

ORPHANS

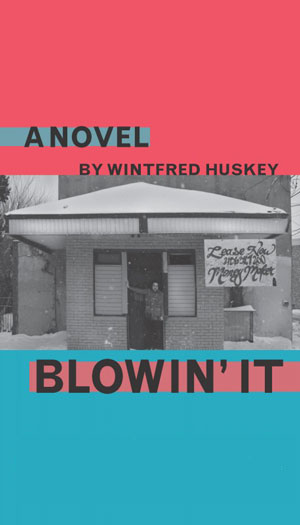

BLOWIN’ IT

BLOWIN’ IT

TOTEMPOLE

TOTEMPOLE

In surrendering to a love that resembles the exchange intimated by the ocean, Stephen relinquishes the guilt that left him feeling like the “disgusting and degenerate” monkeys he observed at the zoo as a child (until their perverse compulsions seemed to reflect his own and he could no longer endure the sight of them).

In surrendering to a love that resembles the exchange intimated by the ocean, Stephen relinquishes the guilt that left him feeling like the “disgusting and degenerate” monkeys he observed at the zoo as a child (until their perverse compulsions seemed to reflect his own and he could no longer endure the sight of them). PANIC IN A SUITCASE

PANIC IN A SUITCASE

THE WOMAN WHO BORROWED MEMORIES

THE WOMAN WHO BORROWED MEMORIES

SISTER GOLDEN HAIR

SISTER GOLDEN HAIR

Devon McReynolds lives in Philadelphia and writes for the Emmy award-winning documentary series “Philadelphia: The Great Experiment.” She holds a B.A. in History from UCLA. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Huffington Post, and the Village Voice.

Devon McReynolds lives in Philadelphia and writes for the Emmy award-winning documentary series “Philadelphia: The Great Experiment.” She holds a B.A. in History from UCLA. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, the Huffington Post, and the Village Voice. ANOTHER MAN’S CITY

ANOTHER MAN’S CITY

THE WILDS

THE WILDS

Kim Steele is a Midwesterner currently living in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in the flash fiction zine Oblong. You can follow her on twitter at KJ_Steele.

Kim Steele is a Midwesterner currently living in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in the flash fiction zine Oblong. You can follow her on twitter at KJ_Steele. CONQUISTADOR OF THE USELESS

CONQUISTADOR OF THE USELESS

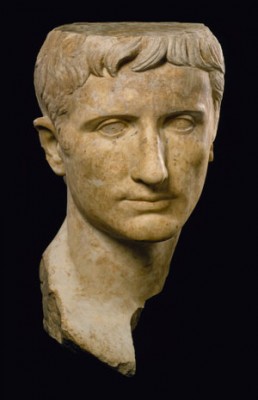

AUGUSTUS

AUGUSTUS Augustus pieces together the life of one of classical Rome’s great Caesars. When he first appears he is a young man, and not much of one. In their memoirs and letters, his friends from youth describe him as slight and sickly. He has an ineffable intensity in his eyes. After his father is murdered, he strategizes his way into popular favor and wins the allegiance of the Roman forces and rules Rome alongside Marcus Antonius and Marcus Lepidus. Eventually, he takes his revenge on Marcus Antonius for the murder. The second half of the book narrates the intrigues of the next decades. Most of these stories revolve around Octavius’ daughter, Julia, his only child, and her relationships with the men who would plot to overthrow the emperor, though unsuccessfully. The letters can be difficult to follow because there are so many names and connections to keep straight. Yet the confusion gives a strong sense of family culture in ancient Rome. This is a world where a man can be criticized who “bears no name, and what virtues he may possess are merely his own.” Many of the letters exchanged in these pages connect family members, and the content of these letters usually drives the plot. But it’s the letters between poets and historians—the letters between friends and colleagues—that sustain the emotionally magnetic pull of this novel.

Augustus pieces together the life of one of classical Rome’s great Caesars. When he first appears he is a young man, and not much of one. In their memoirs and letters, his friends from youth describe him as slight and sickly. He has an ineffable intensity in his eyes. After his father is murdered, he strategizes his way into popular favor and wins the allegiance of the Roman forces and rules Rome alongside Marcus Antonius and Marcus Lepidus. Eventually, he takes his revenge on Marcus Antonius for the murder. The second half of the book narrates the intrigues of the next decades. Most of these stories revolve around Octavius’ daughter, Julia, his only child, and her relationships with the men who would plot to overthrow the emperor, though unsuccessfully. The letters can be difficult to follow because there are so many names and connections to keep straight. Yet the confusion gives a strong sense of family culture in ancient Rome. This is a world where a man can be criticized who “bears no name, and what virtues he may possess are merely his own.” Many of the letters exchanged in these pages connect family members, and the content of these letters usually drives the plot. But it’s the letters between poets and historians—the letters between friends and colleagues—that sustain the emotionally magnetic pull of this novel.

Together, Octavius and Julia are necessary to understand the world of Ancient Rome. As family, they represent the powerful engine of Roman society, and neither of them alone can narratively explain its culture. He wields power quietly and her letters illustrate how that power works. They do so not only in their content, but also in their discursive style. This is nowhere more vivid than in one of the final twists in the plot: Did Julia know about, perhaps even participate in the plot to overthrow Augustus that was organized by several of her former lovers? She certainly admits the motive. In one entry, she writes frankly about her resentment following his decision to marry her off to Tiberius Claudius Nero, an unlikeable fellow who, in the end, claims power after Augustus’ death. When Octavius informs Julia of his plans, she asks him whether all of his personal sacrifices for Roman cohesion have been worthwhile. “I must believe that it has,” he responds, “We both must believe that it has.” His unspoken and personal disbelief is both affirmed and obscured by the imperative to believe. The very same syntax reappears near the end of the book, in Julia’s last entry. In her last conversation with her father he asks her whether she was plotting against him, and she responds: “You must believe that I did not know.”

Together, Octavius and Julia are necessary to understand the world of Ancient Rome. As family, they represent the powerful engine of Roman society, and neither of them alone can narratively explain its culture. He wields power quietly and her letters illustrate how that power works. They do so not only in their content, but also in their discursive style. This is nowhere more vivid than in one of the final twists in the plot: Did Julia know about, perhaps even participate in the plot to overthrow Augustus that was organized by several of her former lovers? She certainly admits the motive. In one entry, she writes frankly about her resentment following his decision to marry her off to Tiberius Claudius Nero, an unlikeable fellow who, in the end, claims power after Augustus’ death. When Octavius informs Julia of his plans, she asks him whether all of his personal sacrifices for Roman cohesion have been worthwhile. “I must believe that it has,” he responds, “We both must believe that it has.” His unspoken and personal disbelief is both affirmed and obscured by the imperative to believe. The very same syntax reappears near the end of the book, in Julia’s last entry. In her last conversation with her father he asks her whether she was plotting against him, and she responds: “You must believe that I did not know.” DUPLEX

DUPLEX

HARLEQUIN’S MILLIONS

HARLEQUIN’S MILLIONS

Elizabeth Mosier is the author of The Playgroup, part of the Gemma Open Door series to promote adult literacy, My Life as a Girl (Random House), and numerous short stories and essays. She has recently completed a new novel, Ghost Signs. Her website is

Elizabeth Mosier is the author of The Playgroup, part of the Gemma Open Door series to promote adult literacy, My Life as a Girl (Random House), and numerous short stories and essays. She has recently completed a new novel, Ghost Signs. Her website is

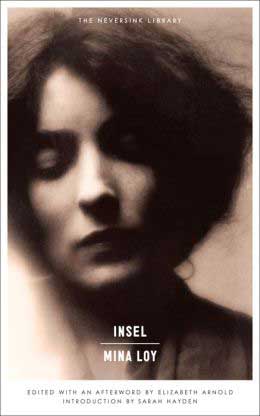

INSEL

INSEL

Lynn Levin’s newest books are the poetry collection Miss Plastique (Ragged Sky, 2013), a Next Generation Indie Book Awards finalist in poetry, and Birds on the Kiswar Tree (2Leaf Press, 2014), a translation from the Spanish of a collection of poems by the Peruvian Andean poet Odi Gonzales. She is co-author of Poems for the Writing: Prompts for Poets (Texture Press, 2013), a Next Generation Indie Book Awards finalist in education/academic books. Her poems, essays, short fiction, and translations have appeared in Painted Bride Quarterly, Michigan Quarterly Review, Cleaver, The Hopkins Review, The Smart Set, Young Adult Review Network, and other places. She teaches at Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania.

Lynn Levin’s newest books are the poetry collection Miss Plastique (Ragged Sky, 2013), a Next Generation Indie Book Awards finalist in poetry, and Birds on the Kiswar Tree (2Leaf Press, 2014), a translation from the Spanish of a collection of poems by the Peruvian Andean poet Odi Gonzales. She is co-author of Poems for the Writing: Prompts for Poets (Texture Press, 2013), a Next Generation Indie Book Awards finalist in education/academic books. Her poems, essays, short fiction, and translations have appeared in Painted Bride Quarterly, Michigan Quarterly Review, Cleaver, The Hopkins Review, The Smart Set, Young Adult Review Network, and other places. She teaches at Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania.