click to return to reviews index

THE NEW YORK NOBODY KNOWS: Walking 6,000 Miles in the City

by William Helmreich

Princeton University Press, 449 pages

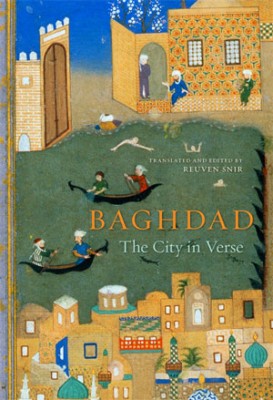

BAGHDAD: THE CITY IN VERSE

edited by Reuven Snir

Harvard University Press, 339 pages

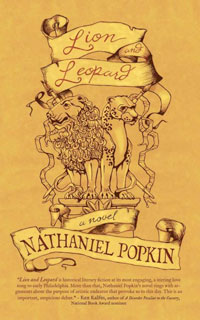

reviewed by Nathaniel Popkin

Writers, this one included, have long struggled to capture in words the dynamic and multi-layered ways that cities change. Cities themselves are powerful change agents in the wider world, but they are defined and redefined constantly by the evolving tastes and desires of their residents (who themselves are always changing), technology, culture and religion, structural political and economic shifts, and the feedback loop of history and history-telling, characterized through myth, poetry, and mass media. Here’s how I try to make sense of it in Song of the City (Four Walls Eight Windows/Basic Books):

click to return to reviews index

Think of the city as a collection of swarming cells that change, adapt, grow, shrink, and grow simultaneously. Imagine hundreds or thousands or millions of cells, each living and dying not in parallel or even in sequence, but overlapping from one generation to the next. The whole place moves in several directions at once. Unless calamity hits, no city dies in a single instant. Despite what you read in the papers, no city, no neighborhood even, is ever miraculously reborn.

I want to say cities change because people, in all their contradictions, make them. But urban change can also be terribly unnerving, even terrifying, and sometimes violent. We might reject it outright, and fight it to the death. We might campaign to preserve a building that harkens to another time, or demand that a neighborhood remains “Italian” or “Puerto Rican” or “black.” And we might mourn for a city “that once was.”

Perhaps, in part, it’s the very conflict between change and constancy that makes cities such interesting and powerful places. Now, two very different but surprisingly related books published at the end of last year, The New York Nobody Knows: Walking 6,000 Miles in the City by William Helmreich (Princeton University Press) and Baghdad: The City in Verse, edited by Reuven Snir (Harvard University Press), help us frame and reframe the discussion. Both Helmreich, a sociologist who has studied New York for four decades and Snir, a professor of Arabic literature at the University of Haifa, seem to agree about the organic nature of urban change. “A city is not a static unit,” writes Helmreich in the introduction to his book. “It’s a dynamic and constantly environment, adapting to the needs of its residents.” Citing the prominent sociologist Janet Abu-Lughod, who passed away a month ago, Snir writes in his excellent introductory essay, “Cities are ‘living processes’ rather than ‘products’ or ‘formalistic shells for living’,” an idea I mirrored in Song of the City, which is organized into parts: pulse, body, soul, and seed.

Both of these admirable new books are indeed necessarily open-ended explorations: Helmreich’s across space, Snir’s through time. Over four years beginning in 2008, New York native Hemreich walked 6,000 miles across nearly every block of New York’s five boroughs; Snir, whose parents were exiled from Baghdad to Israel in 1951, parceled through more than a century of poetry about Baghdad, translating and ultimately presenting 199 poems by some 123 poets.

The cities, too, are distinctly comparable. Baghdad was founded in an instant, in 762, by the Caliph al-Mansur, who called his city Madinat al-Salam, the City of Peace. It was to be the first city in the Arab world that would eschew placelessness. Until then, according to Snir, the Bedouin notion of genealogy framed one’s Islamic self-conception far more than the idea of homeland. Within a century, having made “place and self mutually interdependent,” Baghdad became one of the largest cities in the world, and beyond that, writes Snir, in a manner that makes us think of New York as a symbol for America, “Baghdad has been the city of Islam and Arabism par excellence—the center of the Islamic empire and the Arab world, in reality and certainly metaphorically. Baghdad was at times a metaphor even for the entire East.”

It became an open and pluralistic and hedonistic city through the end of the first millennium, into the second. It was, as the poet Ibn al-Rumi writes in the 9th century, “A city where I accompanied childhood and youthfulness;/ there I wore a new cloak of glory./When she appears in the imagination, I see her budding branches aflutter.” And then, in 1258, the city was destroyed by the Mongol Hulagu, a founder of the Persian dynasty Il-Khanid. This was all but the death of the place; Baghdad didn’t quite recover until the late 19th century into the 20th century, when it flourished as a tolerant, modern metropolis. The Baghdad of a century ago, in 1914, Snir points out, was majority Jewish, and filled otherwise with Arabs, Bedouins, Christians, Kurds, Persians, and Turks. At that very moment, melting pot New York was enjoying the heights of 20th century immigration and the first great migration of African Americans to the more tolerant north.

Of course, Sadaam Hussein and the modern Hulagu, the United States, eventually put that to an end; and in a sense, the cities’ fates became intertwined, as the poet Adonis, whose work on Baghdad Snir has collected in this volume, notes in the poem Salute to Baghdad (2003),

Put your coffee aside and drink something else.

Listening to what the invaders are declaring:

“With the help of God,

We are conducting a preventative war,

Transporting the water of life

From the banks of the Hudson and Thames

To flow in the Tigris and Euphrates

Snir presents a great deal of poetry on Baghdad from the second half of the 20th century and into the 21st, a time marked at first by modernity and cultural blossoming and at last by utter destruction and despair. Writes the poet Bushra al-Bustani in A Sorrowful Melody, “The tanks of malice wander./My wound/Is turned away like an abandoned horse/Scorched by an Arabian sun,/Chewed by worms./Picasso paints another Guernica,/Painting Baghdad under the feet of boors./Freedom is a lute/Strummed by a nameless dwarf./Paintings in Baghdad’s museums/Are at the mercy of the wind.”

In the book’s afterword, the Iraqi writer Abdul Kader el-Janabi notes that with its history of destruction, “Baghdad is an easy metaphor for revival and eclipse.” Indeed, despite attempts to conjure more complex and dynamic narratives for their cities, both Helmreich’s and Snir’s books are infused with that traditional broad stroke urban metaphor, of life and vitality followed by decline and death and (hopefully) life again. The difference is the point of view. New York, in the dusk of the Michael Bloomberg era, is triumphant: safe, utterly vital, nearly entirely tolerant. New York today is New York par excellence. As the protagonist of his story, Helmreich, who grew up in upper Manhattan in the 1950s, carries this prejudice into his exploration, which tends to downplay the challenges to New York’s massive homelessness problem, for example, or ethnic tension. He has a right to, for certain. New York, which lost more than 800,000 people during Helmreich’s formative years, has soared in the last two decades. He is, I think, both proud and amazed. And though Baghdad is now and again one of the largest cities in the Middle East (its population is 7+ million; New York’s is 8.3 million), Snir’s narrative is prejudiced by his own family’s story of loss of a beloved homeland and the war on Iraq, which left vast sections of the city in ruins.

The best way I know to counter the power of this broad, and deeply ingrained, urban narrative is with writing—and in the case of poetry, imagery—that’s specific, and particular to time, place, and circumstance. In this regard, I was somewhat (but only somewhat) disappointed by Snir’s collection. There is much metaphorical writing across the eras—“In the sky/The poles bow,/searching for what deserves illumination,/But the streets are overcrowded/With void.” (Sinan Antoon, 1989)—and not nearly enough visceral reality. I wanted to be taken onto an overcrowded street of the ancient city, of the modern city, of the city post-war to smell and hear and taste it. For that reason, one of my favorites in the collection is An Elegy for al-Sindibad Cinema, by the late Sargon Boulus, published in 2008. The movie house, a fixture of the cosmopolitan city of the mid-20th century, was bombed during the Iraq war. “Those evenings were destroyed…/Our white shirts, Baghdad summers…/How will we dream about traveling to any island?” he asks,

Al-Sindibad Cinema had been destroyed!

Heavy is the watered hair of the drowned person

Who returned to the party

After the lamps were turned off,

The chairs were piled up on the deserted beach,

And the Tigris’s waves were tied by chains.

Helmreich seems aware of this pitfall; his epic walk was meant to—and did—put him face-to-face with hundreds of New Yorkers on their own turf, to see them as individuals whose daily reality helps define the city of today, and who in turn are shaped by the city. And those New Yorkers are complex beings, as he writes, “a person’s identity can include, say, religion, community, race, language, and economic considerations all at once. Human beings are naturally free to pick and choose from these.”

In essence, he’s reporting out on the state of things. In Jamaica, Queens, he meets an immigrant from the small South American country of Guyana who has planted a garden. “It’s a small area,” writes Helmreich, “about four feet long and three feet wide, surrounded by a miniature white picket fence.”

“These flowers are beautiful,” I say by way of starting a conversation.

Small and wiry, with bright teeth framed in part by a neat mustache, he responds with a soft smile, “They are flowers from my country, Guyana, which I love. I planted them to remind me of home. This way, when I look outside I always remember the beautiful place I lived in before I came here.”

Foreign-born people now account for 40 percent of New Yorkers; with their American-born children, Helmreich points out, they are the city’s majority. He thus spends a great deal of time on ethnicity, devoting chapters on new immigrants, “the Future of Ethnic New York,” and on New York’s neighborhood-based communities, home to so much of the immigrant experience.

In the chapter, “Enjoying the City,” Helmreich finds himself in the northwest Bronx, at a concert of the Jamaican reggae singer Beres Hammond. Helmreich describes the scene, “people on their feet, dancing the entire time,” the make-up of the audience—99.9 percent West Indian, 65 percent women—“dressed about two steps above what you’d call casual.” This must have been a fascinating event as cultural tableau. The author might have described in detail food, dress, conversations, art, and even the neighborhood around the venue at CUNY Herbert Lehman College. But instead, Helmreich gives the reader a kind of quick analysis in language that feels too broad and too conjectural (and full of assumptions), hoping to categorize the scene rather than record it for its essence. “Each immigrant who comes to the United States,” he writes,

leaves behind ways of life that need to be adapted to fit in with their new circumstances. Yet they also wish to preserve their identity. Yes, they’re now in America and hearing American music, but also important is the music of the homeland, accompanied by lyrics that express yearning, memories, shared values, and forms of cultural expression—how the houses looked, how the foods tasted, and how the people lived and related to one another. And of course the lyrics speak of the challenges of making it in their new homes.

Helmreich goes on to reveal some of Hammond’s stage banter, but of course what the reader really wants is to read the lyrics that are about the struggle to live in two worlds, hear the conversations, and taste the food. The author has it all, we presume, in his notes, but this visceral, sensatory New York isn’t revealed here. Nor are buildings or streets described in any consistent way. This isn’t Joseph Mitchell; we can’t quite conjure Helmreich’s hidden New York.

Part of the issue here is that the author is too ambitious: he wants to give us the whole city, the city he’d lovingly discovered and rediscovered in his four year walk, but 468 square miles is too vast a territory for ethnography. And his sociologist’s instincts work against him: amidst the panorama, it’s extremely hard to categorize and label in ways that expand the reader’s interest and imagination. To try to make sense of complex things, he’s all too often forced to sweeping judgment and summary statements that feel inadequate. Calling some place a “bad neighborhood” or diverse people “gentrifiers” doesn’t help. Labels have a way of distancing us from the complicated reality.

Interestingly, the book improves vastly as it moves along. In the long chapter on gentrification, Helmreich is able to convincingly put analytic skills to work, and perhaps because the people he encountered in gentrifying neighborhoods are English speaking, the quotes from them are longer and more resonant. It also appears that the systems and values at work in these places feel more accessible to him, and therefore to the reader. But he is right focus so substantially on immigration and immigrant life. Nothing so much defines the process of urban change than the ways newcomers adapt, reject, assimilate, become inspired by the city they’re adopting, which is after all the collective product of the many millions of people who had come before.

Cleaver reviews editor Nathaniel Popkin is the author of five books, including the 2018 novel Everything is Borrowed, and co-editor (with Stephanie Feldman) of the anthology Who Will Speak for America? His essays and works of criticism have appeared in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Kenyon Review, LitHub, Tablet Magazine, and Public Books. If you are an author or publicist seeking reviews or a writer hoping to write reviews for Cleaver, query Nathaniel.

Cleaver reviews editor Nathaniel Popkin is the author of five books, including the 2018 novel Everything is Borrowed, and co-editor (with Stephanie Feldman) of the anthology Who Will Speak for America? His essays and works of criticism have appeared in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Kenyon Review, LitHub, Tablet Magazine, and Public Books. If you are an author or publicist seeking reviews or a writer hoping to write reviews for Cleaver, query Nathaniel.

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Book Reviews.

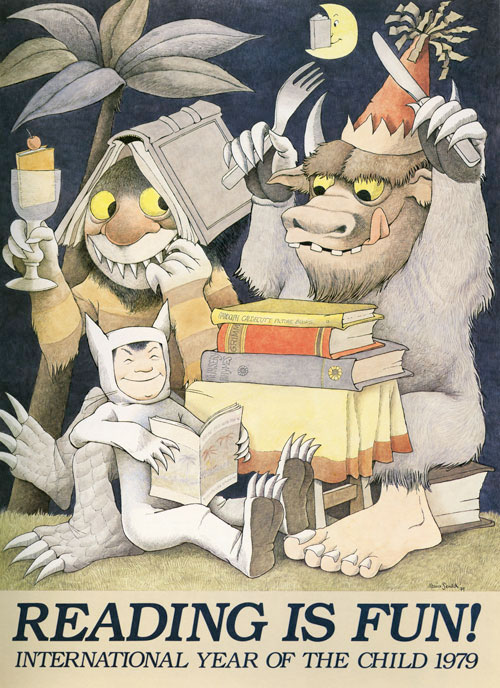

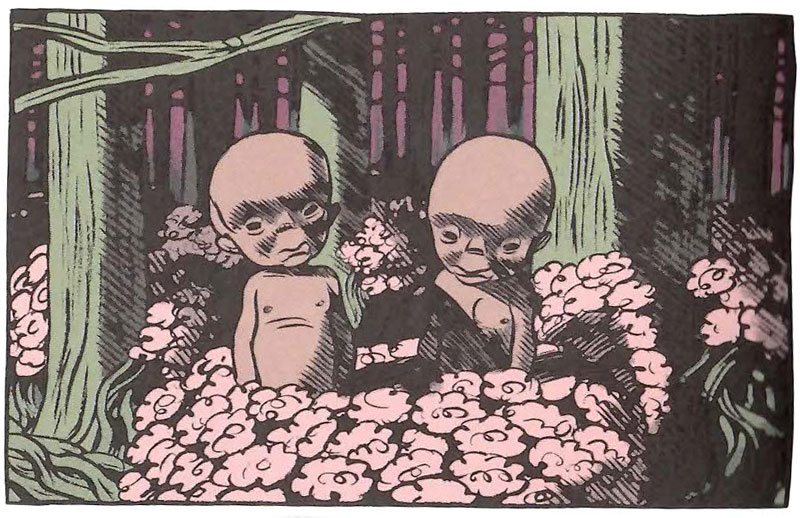

Those of us who grew up reading Sendak’s beloved children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are—which is to say, very many of us—undoubtedly recognize in those words the strange and titillating worldview that belonged to the wolf-suit wearing Max. In a gorgeous 200-plus page coffee table book recently published by Abrams and in conjunction with a 2013 Sendak retrospective, Maurice Sendak: A Celebration of the Artist and His Work, readers can immerse themselves in this vivid worldview. The book is broken up into eleven chapters, each focused on a different theme relating to Sendak’s life and work. There’s a chapter dedicated to the posters Sendak designed (“Sendak used the extra space to stretch out with his favored characters,” explains Steven Heller in the accompanying essay); another chapter tracks Sendak’s work on stage, including his opera design (“Oy gevalt!!” the children’s book author exclaimed when first contacted by the opera director Frank Corsaro, who asked if he’d be interested in collaborating on The Magic Flute); and still another is devoted to his work as an educator (“If you’re going to steal, steal good,” he once told a member of his 1971 Children’s Books course at Yale).

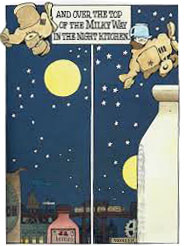

Those of us who grew up reading Sendak’s beloved children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are—which is to say, very many of us—undoubtedly recognize in those words the strange and titillating worldview that belonged to the wolf-suit wearing Max. In a gorgeous 200-plus page coffee table book recently published by Abrams and in conjunction with a 2013 Sendak retrospective, Maurice Sendak: A Celebration of the Artist and His Work, readers can immerse themselves in this vivid worldview. The book is broken up into eleven chapters, each focused on a different theme relating to Sendak’s life and work. There’s a chapter dedicated to the posters Sendak designed (“Sendak used the extra space to stretch out with his favored characters,” explains Steven Heller in the accompanying essay); another chapter tracks Sendak’s work on stage, including his opera design (“Oy gevalt!!” the children’s book author exclaimed when first contacted by the opera director Frank Corsaro, who asked if he’d be interested in collaborating on The Magic Flute); and still another is devoted to his work as an educator (“If you’re going to steal, steal good,” he once told a member of his 1971 Children’s Books course at Yale). These amusing tidbits help us get to know the man who stumbled into the world of children’s literature just before the market for such works exploded in the postwar 1950’s. Born in 1928 to Polish immigrant parents, Maurice, or Moishe, got his start as the assistant window director of FAO Schwartz. Soon he was noticed by Ursula Nordstrom, a woman whom Leonard S. Marcus describes as “America’s most daring publisher of books for young people” at the time. Sendak had already fixed on the object of his artistic explorations. As his cherished works repeatedly reflect, he was fixated on the question of “how children survive in a world largely indifferent to their fate.” In Chapter X, titled Where the Wild Things Are (though wild things manage to show up in almost every Sendak-related project after their 1963 debut), curator Patrick Rodgers has an essay on three preliminary drawings from the children’s book. Comparing early watercolor drawings to the final product, Rodgers shows how Sendak carefully toiled to condense details in order to convey the force of Max’s emotions. Through

These amusing tidbits help us get to know the man who stumbled into the world of children’s literature just before the market for such works exploded in the postwar 1950’s. Born in 1928 to Polish immigrant parents, Maurice, or Moishe, got his start as the assistant window director of FAO Schwartz. Soon he was noticed by Ursula Nordstrom, a woman whom Leonard S. Marcus describes as “America’s most daring publisher of books for young people” at the time. Sendak had already fixed on the object of his artistic explorations. As his cherished works repeatedly reflect, he was fixated on the question of “how children survive in a world largely indifferent to their fate.” In Chapter X, titled Where the Wild Things Are (though wild things manage to show up in almost every Sendak-related project after their 1963 debut), curator Patrick Rodgers has an essay on three preliminary drawings from the children’s book. Comparing early watercolor drawings to the final product, Rodgers shows how Sendak carefully toiled to condense details in order to convey the force of Max’s emotions. Through  changes in posture, expression, and movement, for instance, he transformed the wild things into the objects of Max’s active imagination to emphasize the young boy “as the author of his own cathartic fantasy.” As a teacher, Sendak explained this process of condensation as an attendance to rhythm – how a book could, as Sendak’s student Paul O. Zelinsky recalls, “become music.”

changes in posture, expression, and movement, for instance, he transformed the wild things into the objects of Max’s active imagination to emphasize the young boy “as the author of his own cathartic fantasy.” As a teacher, Sendak explained this process of condensation as an attendance to rhythm – how a book could, as Sendak’s student Paul O. Zelinsky recalls, “become music.”

Tahneer Oksman recently completed her Ph.D. in English Literature at the Graduate Center at CUNY. Her articles on women’s visual culture have been published or are forthcoming in a/b: Auto/Biography Studies, Studies in American Jewish Literature, Studies in Comics, and several upcoming anthologies. She has taught at NYU-Gallatin, Brooklyn College, and Rutgers University in New Brunswick. Currently, she is at work on a manuscript on Jewish women’s identity in contemporary graphic memoirs. She is on faculty at Marymount Manhattan College as Assistant Professor of Writing and Director of the Writing Seminar Program.

Tahneer Oksman recently completed her Ph.D. in English Literature at the Graduate Center at CUNY. Her articles on women’s visual culture have been published or are forthcoming in a/b: Auto/Biography Studies, Studies in American Jewish Literature, Studies in Comics, and several upcoming anthologies. She has taught at NYU-Gallatin, Brooklyn College, and Rutgers University in New Brunswick. Currently, she is at work on a manuscript on Jewish women’s identity in contemporary graphic memoirs. She is on faculty at Marymount Manhattan College as Assistant Professor of Writing and Director of the Writing Seminar Program.

Amy Victoria Blakemore is a graduate of Franklin and Marshall College, where she served for three years as a writing tutor. She earned honors for her senior thesis on contemporary iterations of Superman in comics and graphic literature, and she also was awarded an Academy of American Poetry Prize. Her work appears in the The Kenyon Review, [PANK], and The Susquehanna Review.

Amy Victoria Blakemore is a graduate of Franklin and Marshall College, where she served for three years as a writing tutor. She earned honors for her senior thesis on contemporary iterations of Superman in comics and graphic literature, and she also was awarded an Academy of American Poetry Prize. Her work appears in the The Kenyon Review, [PANK], and The Susquehanna Review.

Cleaver reviews editor

Cleaver reviews editor

Language here is not just a communicative device, it is a forger of connections—connection as preservation and remembrance, connection as assimilation, and connection as the only cord between a boy sailing from Alexandria to Lebanon, a man reciting poetry to himself in the shower, and a man and his wife on a ranch in Arizona. The poetic impulse induces both anxiety when the words won’t come, and profound joy when they will. In “Why I Have the Radio On,” the speaker has forgone a family outing to stay in and work, only the expected “significant work” won’t come:

Language here is not just a communicative device, it is a forger of connections—connection as preservation and remembrance, connection as assimilation, and connection as the only cord between a boy sailing from Alexandria to Lebanon, a man reciting poetry to himself in the shower, and a man and his wife on a ranch in Arizona. The poetic impulse induces both anxiety when the words won’t come, and profound joy when they will. In “Why I Have the Radio On,” the speaker has forgone a family outing to stay in and work, only the expected “significant work” won’t come: Cleaver Magazine reviewer and assistant poetry editor

Cleaver Magazine reviewer and assistant poetry editor

Elizabeth Mosier is the author of The Playgroup (Gemma Open Door) and My Life As a Girl (Random House). She has recently completed a new novel, Ghost Signs.

Elizabeth Mosier is the author of The Playgroup (Gemma Open Door) and My Life As a Girl (Random House). She has recently completed a new novel, Ghost Signs.

Stephanie Trott received a B.A. in English and Creative Writing from Bryn Mawr College in 2012. Her work has appeared in Polaris: An Undergraduate Journal of Literature and Arts, Bryn Mawr’s Nimbus magazine, and the premiere issue of Buffalo Almanack. An aspiring writer and photographer, she presently lives and works in Mystic, CT.

Stephanie Trott received a B.A. in English and Creative Writing from Bryn Mawr College in 2012. Her work has appeared in Polaris: An Undergraduate Journal of Literature and Arts, Bryn Mawr’s Nimbus magazine, and the premiere issue of Buffalo Almanack. An aspiring writer and photographer, she presently lives and works in Mystic, CT.

Vanessa Martini graduated from Bard College in 2012 with a degree in creative writing. She now works as a bookseller in San Francisco, where she eats a lot of avocados and walks everywhere. In the past she has interned for McSweeney’s Lucky Peach, where she milked a cow for an assignment, and for two sex writers, for whom she had to read 50 Shades of Grey.

Vanessa Martini graduated from Bard College in 2012 with a degree in creative writing. She now works as a bookseller in San Francisco, where she eats a lot of avocados and walks everywhere. In the past she has interned for McSweeney’s Lucky Peach, where she milked a cow for an assignment, and for two sex writers, for whom she had to read 50 Shades of Grey.

Kenna O’Rourke is an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania majoring in English with a concentration in Creative Writing. Her work has appeared in The Pocket Guide, the Philos Adelphos Irrealis chapbook, and Penn’s Filament and 34th Street magazines. She is an editorial assistant for Jacket2, an enthusiastic employee of the Kelly Writers House, and

Kenna O’Rourke is an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania majoring in English with a concentration in Creative Writing. Her work has appeared in The Pocket Guide, the Philos Adelphos Irrealis chapbook, and Penn’s Filament and 34th Street magazines. She is an editorial assistant for Jacket2, an enthusiastic employee of the Kelly Writers House, and

Shinelle L. Espaillat writes, lives and teaches in Westchester County, NY. She earned her M.A. in Creative Writing at Temple University. Her work has appeared in Midway Journal.

Shinelle L. Espaillat writes, lives and teaches in Westchester County, NY. She earned her M.A. in Creative Writing at Temple University. Her work has appeared in Midway Journal.

Margaret Galvan is a PhD candidate in English and a film studies certificate candidate at the City University of New York Graduate Center. She is writing a dissertation entitled “Archiving the ’80s: Feminism, Queer Theory, & Visual Culture” that traces a genealogy of queer theory in 1980s feminism through representations of sexuality in visual culture. Her academic writings, which explore the intersection of critical theory and visual representation of female bodies, can be found in publications like the Graphic Novels (Salem Press, 2012) reference work and in the forthcoming book, The Ages of The X-Men (McFarland, 2013). She teaches in the Gallatin Writing Program at New York University and works as an Instructional Technology Fellow at Brooklyn College. See

Margaret Galvan is a PhD candidate in English and a film studies certificate candidate at the City University of New York Graduate Center. She is writing a dissertation entitled “Archiving the ’80s: Feminism, Queer Theory, & Visual Culture” that traces a genealogy of queer theory in 1980s feminism through representations of sexuality in visual culture. Her academic writings, which explore the intersection of critical theory and visual representation of female bodies, can be found in publications like the Graphic Novels (Salem Press, 2012) reference work and in the forthcoming book, The Ages of The X-Men (McFarland, 2013). She teaches in the Gallatin Writing Program at New York University and works as an Instructional Technology Fellow at Brooklyn College. See

Roberta Fallon is the co-founder of t

Roberta Fallon is the co-founder of t

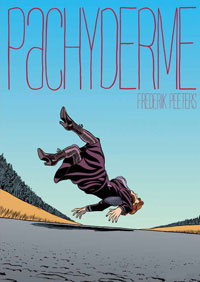

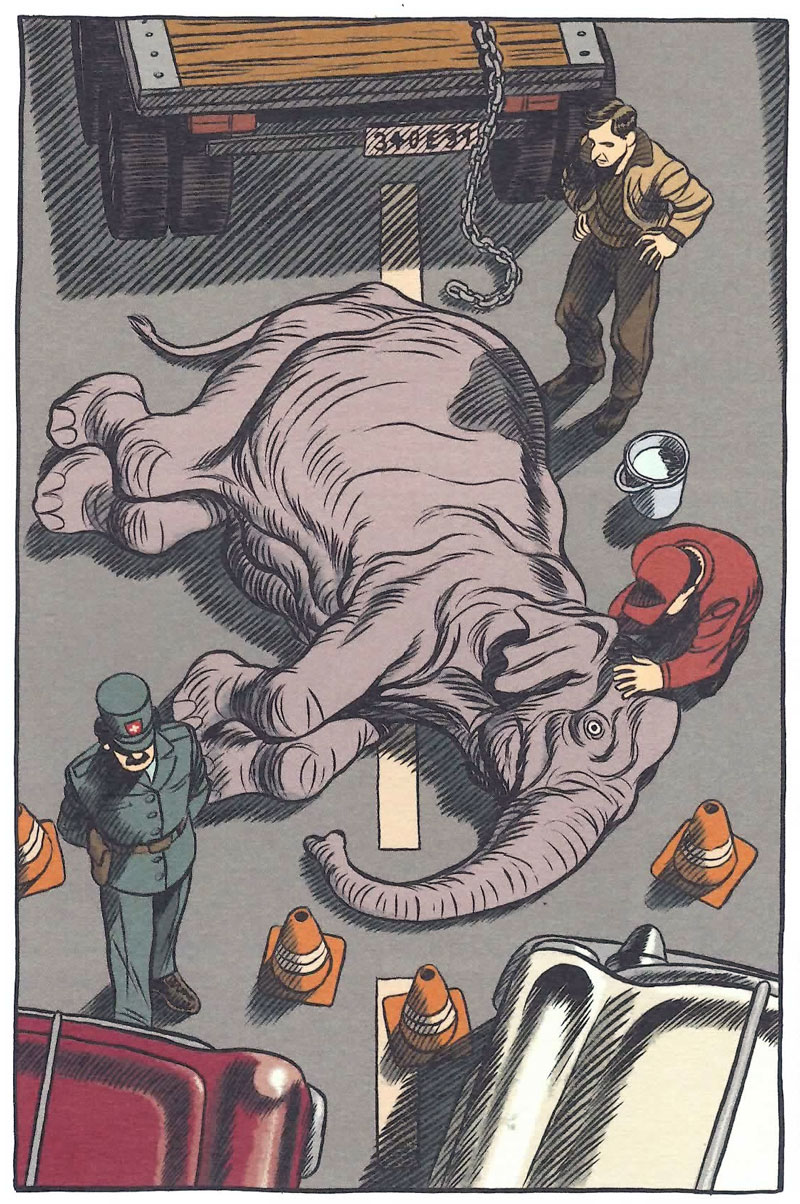

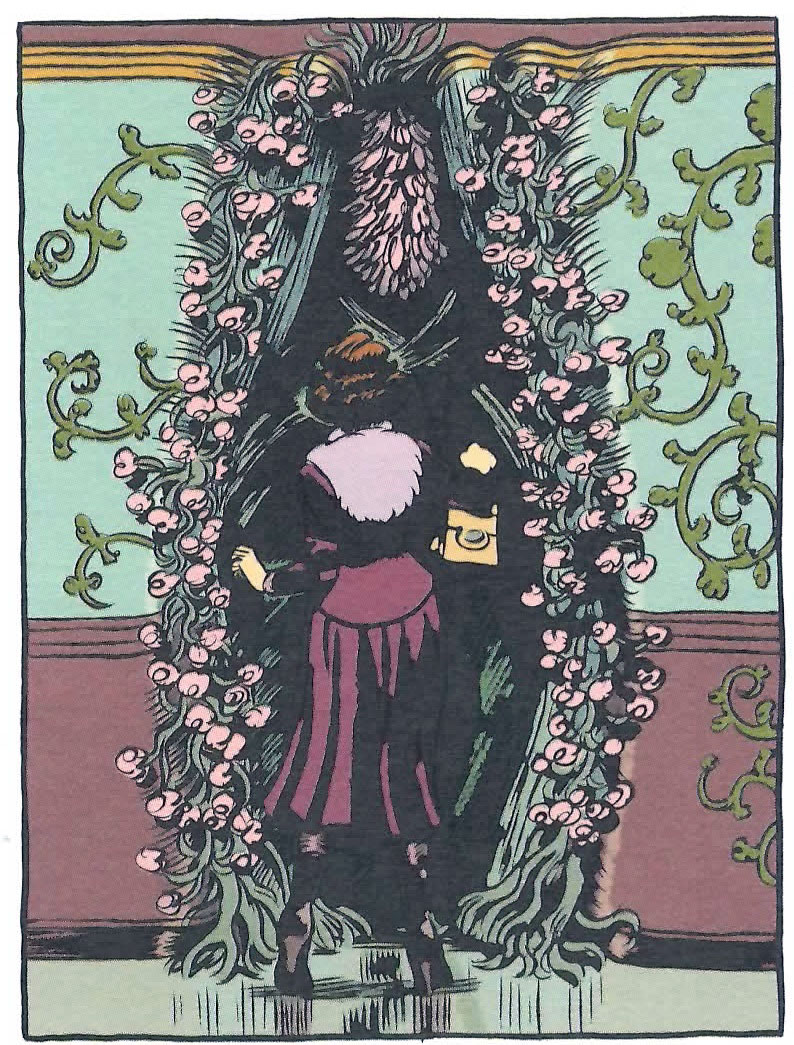

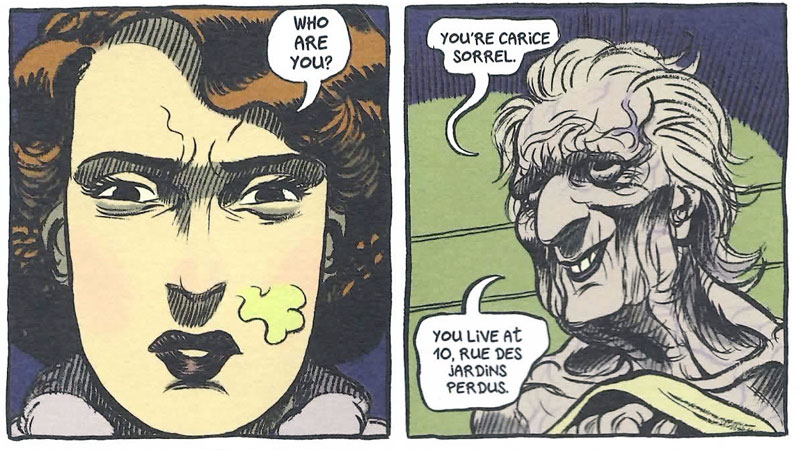

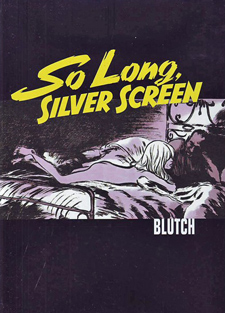

He is after some documents, and enlists Carice’s help to retrieve them, or at a minimum to convince doctor Barrymore in the hospital to return them. This other character, the doctor, has his own depthand it almost rivals Carice’s, though he appears in fewer pages. He is an enigma, a dancing alcoholic seducer of women who seemingly likens his craft to performance. His is another path with which to read and analyze the comic.

He is after some documents, and enlists Carice’s help to retrieve them, or at a minimum to convince doctor Barrymore in the hospital to return them. This other character, the doctor, has his own depthand it almost rivals Carice’s, though he appears in fewer pages. He is an enigma, a dancing alcoholic seducer of women who seemingly likens his craft to performance. His is another path with which to read and analyze the comic. Brazos Price is from Austin, Texas where he served as an inaugural member of the Texas Library Association’s Maverick Graphic Novel Reading List. He has also reviewed comics for the librarian focused website

Brazos Price is from Austin, Texas where he served as an inaugural member of the Texas Library Association’s Maverick Graphic Novel Reading List. He has also reviewed comics for the librarian focused website

Vanessa Martini graduated from Bard College in 2012 with a degree in creative writing. She now works as a bookseller in San Francisco, where she eats a lot of avocados and walks everywhere. In the past she has interned for McSweeney’s Lucky Peach, where she milked a cow for an assignment, and for two sex writers, for whom she had to read 50 Shades of Grey.

Vanessa Martini graduated from Bard College in 2012 with a degree in creative writing. She now works as a bookseller in San Francisco, where she eats a lot of avocados and walks everywhere. In the past she has interned for McSweeney’s Lucky Peach, where she milked a cow for an assignment, and for two sex writers, for whom she had to read 50 Shades of Grey.

The older boy immediately noticed the little boy’s gaze; he gestured to him and the mother let him out of the stroller. She smiled with delight as the Palestinian boy held out the kite handle and the two boys held on together, the older one keeping a casual eye on the kite, tugging and guiding, the younger one concentrating hard on the string.

The older boy immediately noticed the little boy’s gaze; he gestured to him and the mother let him out of the stroller. She smiled with delight as the Palestinian boy held out the kite handle and the two boys held on together, the older one keeping a casual eye on the kite, tugging and guiding, the younger one concentrating hard on the string.

William Boyle is from Brooklyn, NY and lives in Oxford, MS. His writing has appeared in The Rumpus, L.A. Review of Books, Salon, Hobart, and other magazines and journals. His first novel, Gravesend, is forthcoming from Broken River Books.

William Boyle is from Brooklyn, NY and lives in Oxford, MS. His writing has appeared in The Rumpus, L.A. Review of Books, Salon, Hobart, and other magazines and journals. His first novel, Gravesend, is forthcoming from Broken River Books.

Chris Ludovici has published articles in The Princeton Packet and online at Cinedelphia. His fiction has appeared in several literary magazines, and in 2009 he won the Judith Stark awards in fiction and drama. He has completed three novels, two on his own and one with his wife Desi whom he lives with along with their son Sam and too many cats in Drexel Hill.

Chris Ludovici has published articles in The Princeton Packet and online at Cinedelphia. His fiction has appeared in several literary magazines, and in 2009 he won the Judith Stark awards in fiction and drama. He has completed three novels, two on his own and one with his wife Desi whom he lives with along with their son Sam and too many cats in Drexel Hill.

Mary Weston is a native of Philadelphia who graduated from Bard College in 2012 with a degree in literature and a concentration in contemporary poetry and poetics. Currently, she works at a non-profit that deals with adult literacy issues in Philadelphia. In her free time, she can be found reading, writing, or exploring the city on her bicycle.

Mary Weston is a native of Philadelphia who graduated from Bard College in 2012 with a degree in literature and a concentration in contemporary poetry and poetics. Currently, she works at a non-profit that deals with adult literacy issues in Philadelphia. In her free time, she can be found reading, writing, or exploring the city on her bicycle.