Robert Sorrell is a writer and photographer living in Philadelphia. He recently graduated from the University of Chicago’s English program and has a piece of narrative nonfiction forthcoming from Mosaic Art & Literary Journal.

Robert Sorrell is a writer and photographer living in Philadelphia. He recently graduated from the University of Chicago’s English program and has a piece of narrative nonfiction forthcoming from Mosaic Art & Literary Journal.

I’M FINE. HOW ARE YOU? a chapbook by Catherine Pikula, reviewed by Robert Sorrell

I’M FINE. HOW ARE YOU? by Catherine Pikula Newfound, 46 Pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell A few days after I finished Catherine Pikula’s chapbook I’m Fine. How are You? I read the following sentence: “I would like to make a book out of crumpled-up pieces of paper: you start a sentence, it doesn’t work and you throw the page away. I’m collecting a few … maybe this is, in fact, the only literature possible today.” The sentence came in the last hundred pages of The Story of a New Name, the second book in Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. And while the “today” referenced above was Italy in the 1960s, the description was oddly reminiscent of the small, thread-bound chapbook published in 2018 that I’d recently put down, I’m Fine. How Are You? Composed in a fine but digressive and fragmented prose, with short sections ranging from a few paragraphs to a few lines, I’m Fine. How Are You? is a work that doesn’t fit neatly into any one genre. “‘Is it a Lyric Essay? Is it a Long Poem? Is it Meditations?’” wonders poet Matthew Rohrer in a blurb for the book, but Pikula doesn’t seem interested in parsing genre ...

AFTER THE WINTER, a novel by Guadalupe Nettel, translated by Rosalind Harvey, reviewed by Robert Sorrell

AFTER THE WINTER by Guadalupe Nettel translated by Rosalind Harvey Coffee House Press, 242 Pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell Purchase this book to benefit Cleaver At the beginning of Guadalupe Nettel’s newly translated novel After the Winter, twenty-five-year-old Cecilia moves from her native Oaxaca to Paris. She arrives there without the usual image of Paris as a “city where dozens of couples of all ages kissed each other in parks and on the platforms of the métro, but of a rainy place where people read Cioran and La Rochefoucauld while, their lips pursed and preoccupied, they sipped coffee with no milk and no sugar.” However, there is something usual in her expectation for Paris. “Like many of the foreigners who end up staying for ever […] with the intention, or rather, the pretext of studying a postgraduate degree,” she takes up residence across the street from Père Lachaise cemetery, final resting place of Jim Morrison, Oscar Wilde, and Edith Piaf. “At different periods in my life, graves have protected me,” Cecilia shares, and the small apartment overlooking the cemetery suits her macabre nature perfectly. Cecilia is one of the two first-person narrators in After the Winter, the other being Claudio, ...

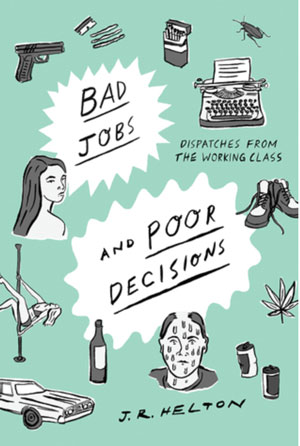

BAD JOBS AND POOR DECISIONS Dispatches from the Working Class, a memoir by J.R. Helton, reviewed by Robert Sorrell

BAD JOBS AND POOR DECISIONS Dispatches from the Working Class by J.R. Helton Liveright Publishing Corporation, 259 Pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell The jacket of J.R. Helton’s memoir, Bad Jobs and Poor Decisions: Dispatches from the Working Class, shows an assortment of loose black-and-white sketches: a marijuana leaf, a packet of cigarettes, a typewriter, crumpled beer cans, lines of (presumably) cocaine, a gun, a cockroach. Among them, figures emerge: A man’s face covered in huge beads of sweat, a woman with long dark hair shown from the shoulders up, a pole dancer. These images appear regularly in each of the seven long anecdotes that make up Bad Jobs, working as signifiers of a place, time, and social class. The place is Austin, Texas and the time is when the tail end of the 1970s met the Reagan 1980s. The class setting is a bit more complicated, but I’ll get to that later. When we meet J.R. Helton—or Jake, as his character is known in the book—he’s a 20-year-old writer who’s just dropped out of the University of Texas in Austin to write full time after winning a small literary prize. “I thought, Man, this is gonna be easy,” Helton writes, ...

BIRTH OF A NEW EARTH: The Radical Politics of Environmentalism, a manifesto by Adrian Parr, reviewed by Robert Sorrell

BIRTH OF A NEW EARTH: The Radical Politics of Environmentalism by Adrian Parr Columbia University Press, 328 Pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell Near the beginning of his ecstatic, beautiful “Poem to My Child, If Ever You Shall Be,” Ross Gay writes: I wonder, little bubble of unbudded capillaries, little one ever aswirl in my vascular galaxies, what would you think of this world which turns itself steadily into an oblivion that hurts, and hurts bad? Would you curse me my careless caressing you into this world or would you rise up and, mustering all your strength into that tiny throat which one day, no doubt, would grow big and strong, scream and scream and scream until you break the back of one injustice, or at least get to your knees to kiss back to life some roadkill? I first read this poem as Hurricane Harvey and Maria devastated the Caribbean and parts of the southern United States. The poem captivated me. In Gay’s steady hands the prospect of the future, symbolized by this possible child, is explored with deep empathy, imagination, and emotional complexity. The question at the center of these stanzas—how would a child react to being ...

MALACQUA, a novel by Nicola Pugliese, reviewed by Robert Sorrell

MALACQUA by Nicola Pugliese translated by Shaun Whiteside And Other Stories Publishing, 198 Pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell It begins with the sea. Out the windows, down the alleys, on the perpetual edge of the city’s consciousness. In Nicola Pugliese’s Naples, the sea is everywhere. “From the street,” he writes, “loneliness falls gracefully away to the sea.” A few years before the main events of Malaqua transpire the government and police of Naples decide to block access to the beach on a beautiful summer day. For a while, the children stare angrily at the line of police along the shore. Eventually the children slink back into the shade and despair of their homes and courtyards. But the sea, not one to be defeated by local government, begins to rise. It rises until it reaches the first row of houses, then moves farther into the city, leaking into basements, waterlogging wooden boards, wetting socks and shoes and the hems of dresses and pants. The police come to realize they cannot guard the sea, and so they leave. “This had in all likelihood been an alert, a warning significant in its way,” the narrator informs us. The alert is for the events ...

THE COLLECTED ESSAYS OF ELIZABETH HARDWICK reviewed by Robert Sorrell

THE COLLECTED ESSAYS OF ELIZABETH HARDWICK by Elizabeth Hardwick edited by Darryl Pinckney New York Review Books, 640 Pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell Reviewing Elizabeth Hardwick’s new collection of essays is a task to strike fear into the heart of even the most headstrong literary critic. Biographer of Melville, co-founder of the New York Review of Books, and noted sharp tongue, Elizabeth Hardwick cast a long shadow in the literary world of the twentieth century. Darryl Pinckney introduces Hardwick in this volume as a New York intellectual firebrand, an avant-garde thinker with an acerbic writing style, and a cutting, devastatingly smart critic who employed a withering gaze. Would-be reviewers, if not scared off by Hardwick’s biography, will encounter an essay in the book’s first hundred pages, “The Decline of Book Reviewing,” which is destined to have some effect on their confidence. If reading that piece is not sufficient, the reviewer will then bump into a piece on a Hemingway biography that begins, “Carlos Baker’s biography of Ernest Hemingway is bad news.” To be blunt, Hardwick, a writer of fiction herself in addition to criticism and biography, does not go easy on writers. The task of reviewing her new collection, once ...

LATE FAME, a novella by Arthur Schnitzler, reviewed by Robert Sorrell

LATE FAME by Arthur Schnitzler translated by Alexander Starritt New York Review Books, 136 Pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell Herr Eduard Saxberger lives in a pleasant apartment overlooking the Vienna Woods. Each night after spending the day in his civil service office, he eats at his usual restaurant where he interacts little with his companions beyond small talk and basic requests, and goes for a walk. His life is stable, if a bit empty. But one day a young man named Wolfgang Meier appears at the door, clutching a copy of the Wanderings, poems by Eduard Saxberger, and the somewhat bumbling, bourgeois civil servant is thrown back into a past he hardly remembers. “You’ve read my Wanderings?” Saxberger exclaims, “People still read my Wanderings?” “People might not read them any more,” rejoins Meier, “but we read them.” And so begins, Late Fame, Arthur Schnitzler’s satire of Fin de Siecle Vienna, published in the U.S. for the first time more than a century after it was written. Just barely hitting the hundred page mark, Late Fame is short, even for a novella, but Schnitzler’s writing is powerful in its simplicity. Characters and images are pinned up like butterflies on a ...

FAMILY LEXICON, a novel by Natalia Ginzburg, translated by Jenny McPhee, reviewed by Robert Sorrell

FAMILY LEXICON by Natalia Ginzburg translated by Jenny McPhee New York Review Books, 224 Pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell Right before falling asleep, my father becomes totally incoherent. If you speak to him, he will respond with words, they just won’t make any sense. Neither will he have any memory of your conversation. (He passed this trait on to me; often to my detriment, I employ it regularly.) Once, when my dad had floated off into this near-unconscious state, he started talking about the Secret Service. From that point on, to spout these nocturnal babblings has become known in my family as “Secret Servicing.” Families, social groups, and even workplaces often have phrases and words just like these. “Inside jokes” is a common term for some of them, but not all fall neatly into this category. For many of these words and phrases, a new definition or usage, with nuance beyond the punchline, has been created for a small group of people. This idea is the cornerstone of Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon. Now in a new translation by Jenny McPhee (and with a new English title), Family Lexicon is Natalia Ginzburg’s Strega Prize winning memoir/novel of life in Italy before, ...

ATLANTIC HOTEL, a novel by João Gilberto Noll, reviewed by Robert Sorrell

ATLANTIC HOTEL by João Gilberto Noll translated by Adam Morris Two Lines Press, 138 pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell “Love. Call me Love, the Word Incarnate.” This is the closest that readers get to a name for the protagonist and narrator of João Gilberto Noll’s strange little book, Atlantic Hotel, recently translated into English by Adam Morris. The novel is set in Brazil in the 1980s, and over the course of the book, the unnamed narrator embarks on a beguiling and pointless quest through the country. At different points he will seem to be—or perhaps will be—an actor, a priest, an alcoholic, an invalid. Along the way, Noll will shade his experiences with touches of Don Quixote and Odysseus, hints of The Stranger and a taste of the pantomime and absurdity of Fellini’s early 1960s films (Noll’s unnamed narrator a believable stand-in for the existentially angsty characters usually played by Marcello Mastroianni). And yet for all the interesting things that could be said about Atlantic Hotel, this review is written in shadow. On March 29, 2017, just a little over a month before the release of the new English translation of Atlantic Hotel, João Gilberto Noll passed away in his ...

SHOT-BLUE, a novel by Jesse Ruddock, reviewed by Robert Sorrell

SHOT-BLUE by Jesse Ruddock Coach House Books, 224 Pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell A few years ago, I had the opportunity to see Winter’s Bone author Daniel Woodrell do a reading and Q&A. His performance was about what you might expect for a reclusive writer hailing from the forgotten hillbilly pocket that is the Ozarks, an area of steep hills and spidery lakes in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas. He had a funny goatee and spoke with an accent that most people in America probably don’t even know exists, twangy yet somehow refined and oddly beautiful, a bit like his novels. Those novels almost all focus on poor rural people who struggle with drugs, the loss of parents, and deep pain, yet they are shot through with a breathtaking lyricism. He opens Winter’s Bone: Ree Dolly stood at break of day on her cold front steps and smelled coming flurries and saw meat. Meat hung from trees across the creek. The carcasses hung pale of flesh with a fatty gleam from low limbs of saplings in the side yards. Three halt haggard houses formed a kneeling rank on the far creekside and each had two or more skinned torsos dangling ...

THESE ARE THE NAMES, a novel by Tommy Wieringa reviewed by Robert Sorrell

THESE ARE THE NAMES by Tommy Wieringa translated by Sam Garrett Melville House, 231 pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell The hero–or perhaps I should say anti-hero–of Dutch author Tommy Wieringa’s new novel, These Are the Names is a 53-year-old police chief named Pontus Beg. Beg lives in a fictional border town called Michailopol, a city ailing in post-Soviet corruption and aimless malaise. Beg has “set up his life as a barrier against pain and discomfort,” Wieringa writes. “Suppressing chaos: washing dishes, maintaining order. What did it matter that one day looked so much like the other that he could not recall a single one; he keeps to the middle equidistant from both bottom and top.” Beg’s life is governed by habit, by a desire to stay “in the middle.” In order to keep things in line, he creates rules for himself. When he drinks he allows himself four glasses of vodka but never five. Once a month he sleeps with his housekeeper, when she is less likely to become pregnant. He still drives an old service vehicle, refusing to steal a newer car as many of his subordinates have. He lives amidst the corruption of the police force without actively ...

The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable by Amitav Ghosh reviewed by Robert Sorrell

THE GREAT DERANGEMENT: Climate Change and the Unthinkable by Amitav Ghosh The University of Chicago Press, 196 pages reviewed by Robert Sorrell Almost exactly a year ago, I walked into a large lecture hall at the University of Chicago and found a seat near the back. The hall was half full, an equal mix of students and professors waiting for the novelist Amitav Ghosh to take the stage. Emerging from the wings, Ghosh gave off a dignified air in his black Nehru vest, his hair shockingly white. When he began to speak however, any trace of austerity, of distance between the speaker and the crowd, disappeared. His voice was soft and surprisingly pleasant, so much so that I began to wonder if he narrated his own audiobooks (he doesn’t). His subject, somewhat to my surprise, was climate change. The lectures can still be found on YouTube, and were recently published in book form with the title The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. In the work, Ghosh argues that future generations will see our cultural response to climate change as one of denial and avoidance, bordering on the pathological. Our failure to acknowledge the dire position in ...