David Hallock Sanders

IF YOU DO NOT KNOW: Excerpt from BUSARA ROAD, a novel in progress

“King Solomon was a very wise man. This we all know. How do we know this? Because the Bible tells us so! Right here in ….”

Pastor Hesborne Kabaka made a small production out of opening his Bible and reading from it.

“…right here in the book of the Wisdom of Solomon. There you go—clear as can be!”

Someone in the congregation exhaled a soft laugh. The pastor shut his Bible.

“So…we know that Solomon is wise. We know there are many, many stories of his wisdom. But how did he become such a wise man? What was the source of his wisdom?”

The pastor let the question hang in the hot, humid air of the chapel. The smell of sweating bodies mixed with a scent of cow dung wafting in the open windows. Mark found the sour-sweet blend surprisingly pleasant.

He was attending his first Sunday service at the Friends Church. Mark had arrived just days before at the Kwetu Quaker Mission, a modest clutch of cinderblock-and-tin buildings high in the equatorial rainforest of western Kenya. It was just three years ago that the country had gained its independence. Only a year ago that Mark’s mother had died. Mere months since his father had accepted the job to support Quaker schools for the newly independent nation.

“A fresh beginning,” his father had called the three-year appointment. “For Kenya. For us.”

Pastor Kabaka answered his own question.

“The source of Solomon’s wisdom was the source of all wisdom…God!” The pastor shouted the name of the Almighty. “When Solomon became the king of Israel, God came to him in a dream and said, ‘What do you want from me? Would you like great wealth? Would you like great fame?’ And Solomon said, ‘No, Lord! I only ask you for wisdom. I am facing many great challenges and responsibilities. Please give me the wisdom and knowledge to rule my people well.’”

The pastor trilled his r’s like thunder.

So far, little of this Kenyan service had resembled Mark’s Quaker meeting in Philadelphia. In Philadelphia, the service was an hour of silent worship only occasionally punctuated by spoken ministry. Anyone in the meeting could speak from the silence, as long as he or she felt led by the Spirit. Some weeks, no one spoke at all. There was no music, no singing, and certainly no one standing at a pulpit waving the Bible above his head.

“Solomon’s respect and humility greatly pleased the Lord.” The pastor’s voice dropped to nearly a whisper. “How could you not love a man like that! So the Lord said, ‘I will give you what you ask for—wisdom, knowledge, and common sense. And because I like you, I will add the wealth and fame for free!’”

Mark couldn’t remember ever hearing laughter at his meeting back home.

“So now…” the pastor’s voice began to rise. “What is our Swahili word for wisdom? For understanding and common sense?”

Mark heard a cowbell outside.

“That word is Busara.” Pastor Kabaka nodded as though letting the congregation in on a secret. “And what is the name of the road that runs directly beside this house of worship?”

A few congregants whispered the word.

“Correct! Busara Road. You see? Right now, we are on the very road to wisdom and understanding. And right here…” He lifted the Bible above his head. “…we have the road map!”

The pastor removed a white handkerchief from inside his black suit coat. He carefully unfolded it and wiped his brow.

Mark was sitting toward the back of the chapel next to his father on a long wooden bench. The chapel was filled with a mix of Africans and whites. Some of the African women held babies in their arms or small children at their sides. He recognized a few grownups from the Fourth of July party his first night there, but he saw only two of his classmates—Darrel and Mathew. He wondered if the other children were all skipping church.

Mr. Mbote was seated near the front, but his daughter, Layla, wasn’t with him. Also near the front, but on the opposite side, sat a man dressed in a suit. He had a square head and looked familiar, but it wasn’t until he turned his head and Mark saw his thin mustache that Mark realized it was Mr. Okwiri, the man from the Industrial with the missing arm. Mr. Okwiri caught Mark’s eye, but Mark turned away.

Mark’s bench was just like the benches at his Quaker meeting house back in the States—long, hard, and uncomfortable. The whole chapel was similar to his Friends meeting. Simple white walls. A weathered wood floor. A small balcony at the back. Rows of windows on both sides. Benches in the middle.

But there were also a lot of differences. Instead of the benches facing each other from all four walls, they were lined up in one direction. Instead of a facing bench up at the front for the clerk and other meeting elders, a series of steps led up to a raised platform and a low brick wall decorated with flowers. Behind the wall stood a tall-backed wooden chair beside a pulpit, where Pastor Kabaka carefully folded his kerchief in fours and returned it to his pocket.

“Now!” he continued, his voice filling the chapel. “Let us say that you are living someplace in Kenya. Not here in Kwetu. Someplace far away. Let us say…Nairobi. And let us say that you want to come visit us here in Kwetu, but you have never been here before. Maybe someone in your family lives here now. You want to come visit, but you do not know the way. So what do you do? Do you go and find a map of Tanzania or Uganda to consult? No! What good would that be? Or do you go and ask directions from a friend who has never been to Kwetu? Someone who does not know the way? Of course not!

“If you want to find your way, you must consult the correct map. You must ask the correct friend to guide you.”

The pastor took a deep breath, then his voice boomed across the room:

“It is just the same with your life!”

He leaned over the pulpit and let his eyes pass slowly over the congregation. He looked deeply pleased to see everyone’s eyes on him. He nodded as though he were about to share some special secret.

“To find your way, my friends, you must trust in the wisdom of your guide.”

His voice was a whisper, but everyone could hear.

“To find your way, you must trust in the correctness of your map.”

His voice began to rise.

“And who is your guide? God is your guide! And what is your map? The Holy Bible is your map! God’s wisdom is your map! James 1:5 says, ‘If any of you lacks wisdom; let him ask of God who gives to all men generously.’ God will provide! If we desire wisdom we must ask God — humbly and deeply in faith — to grant us that wisdom!

“Let us pray.”

Mark looked around the chapel. All heads were bowed, even his father’s.

Maybe this was when they did the silent part? Mark had been told by his father that Quaker worship in Kenya had less silence than his unprogrammed meeting in Philadelphia. So far, though, there hadn’t been any silence at all.

He took a slow breath, exhaled, and let his focus soften. Back in the States, Mark had a private game he liked to play in meeting for worship. He called it, “Catch the Spirit.” It was a simple game. During the silence of worship, he tried to guess who would be the next person to stand and speak. He imagined the silence as a pool of still water, and the leading of the Spirit as a ripple in the stillness. Sometimes it was easy to guess. Somebody’s breathing changed or someone’s body shifted. But other times it was much more subtle—like an electric current in the air that circled the room until it settled on one person or another.

Today, though, all he was sensing was the sound of voices drifting in the open windows and the smell of smoke and dung from outside.

“Amen,” said Pastor Kabaka.

“Amen,” the congregation echoed.

That was it? That was the entire silent worship?

“And now,” the pastor gestured to someone in the front row. “Imani, if you please?”

An elegant woman in a long, blue dress rose from the bench. A soft chime rang from the rows of bracelets that shined brightly against the black of her skin. She stood by the pastor’s side.

“My dear wife,” said Pastor Kabaka, “may not have the wisdom of Solomon…”

The woman fluttered her hands, and her bracelets chimed like bells.

“…but the good Lord granted her a beautiful voice. Imani will now sing, ‘The Wise Man Built His House upon the Rock.’ When she has concluded, we invite any children still among us to join Teacher Salama and the others in Sunday school.”

Mark stepped tentatively through the open doorway. Imani’s hymn was still echoing in his head.

The wise man built his house upon the rock,

The wise man built his house upon the rock,

The wise man built his house upon the rock,

And the rain come tumbling down…

The dining hall was filled with children scattered in clusters on the floor. Some sat atop the long tables lined up in a row down the middle of the room.

The rain come down

And the floods come up

And the wise man’s house stands firm.

Some of the children stopped what they were doing to register the arrival of Mark, Darrel, and Mathew. Mark noticed Sarah and Robin playing some kind of hand game at the far side of the dining hall. They glanced in his direction, then returned to their game.

An African boy, sitting on the floor with a book in his lap, jumped to his feet and ran to greet Mark. He was Mark’s age and Mark’s height, dressed in tan shorts and a white tee-shirt. His skin was dark, almost a bluish black, and his hair was a closely cropped nest of black curls. His eyes were wide and bright, and a smile lit up his face as though he recognized Mark.

“I’ve been waiting for you! I saved you food.”

Mark was confused. He didn’t know the boy.

“Your name is Mark,” the boy continued without waiting for a response. “My name is Radio. My father is the doctor. Do you want to play together?”

A tall woman approached from the far end of the room. She wore a long brown dress with a yellow apron. Her hair was a waterfall of black strands tied at the back.

The woman placed her hand atop Radio’s head and gave him a gentle warning glance.

“Raymond, if you please,” she said. “Give our new friend some room to breathe.”

She extended her hand to Mark.

“Welcome! I am Teacher Salama. Salama Mwendia, your Sunday school tutor. And you must be Mark. We are very pleased you have joined us. In future, you may attend the opening of chapel as you have this morning, or you may come directly here for Sunday classes. I save my Bible studies until all the children have gathered. But do not fear, it is not so serious as it sounds! We also enjoy many games and art projects, as well as refreshments. You will find that we manage to have some fun while we are learning the Lord’s lessons.”

Salama put a gentle arm around Mark’s shoulder and led him toward the waiting group.

“I believe you have already met most of the American children. And Radio has lost no time in making his presence known. But let me introduce you to the others.”

“I’ll do it!” said Radio.

Mark’s father sat on the edge of the bed, reading aloud by the light of the single lamp. His voice was accompanied by the night sounds of the jungle—the rhythmic hissing of cicadas, the rasping of frogs, the occasional chuck-chuck-chucking of some larger animal.

It had been a long day, and Mark was already tucked beneath the mosquito net and under his covers. He felt safe here in bed, as though the netting not only protected him from mosquitos, but kept all dangers at bay.

His eyes were heavy and sleep was near, but he wanted to stay awake for the end of the chapter.

“When the monkey groom was announced,” his father read, “the Jade Emperor said, ‘Come forward Monkey. I hereby proclaim you Great Sage, Equal of Heaven.’”

Tonight’s chapter had followed the latest exploits of the stone Monkey as he journeyed through the Southern Gate of Heaven. Mark’s father had started reading the Chinese folk tale to him back in the States, and Mark was happy they’d finally returned to Monkey’s adventures. Monkey had already talked his way past heaven’s Guardian Deities, gotten himself appointed keeper of heaven’s stables, and then, insulted by the lowness of his position, abandoned his post and returned to earth where he fought a series of battles with magic spirits sent to arrest him. Monkey was finally tricked into returning to heaven by the Jade Emperor’s offer of an honorary title.

Mark wished he were more like Monkey. Always ready to take risks. Always ready to rock the boat and do what he wanted. Never worried about disappointing or messing up. Never scared.

“‘The rank is a high one,’” His father intoned the Emperor’s deep voice. “‘And I hope we shall have no more nonsense.’”

Mark yawned and rolled onto his side. He blinked rapidly to keep from falling asleep. He didn’t want to miss his favorite part: the final words that closed each chapter.

His father’s body was warm next to Mark’s. A single lamp lit the book in his hands. A moth beat at the window. Sleep gently pulled and pulled as his father read.

“Monkey was begged not to allow himself to get in any way excited or start again on his pranks. But as soon as he arrived, he opened both jars of Imperial wine and invited everyone in his office to a feast.”

Mark could sense the chapter’s end was near. He studied his father’s face, its features softened by the dim light.

“The star spirit went back to his own quarters, and Monkey, left to his own devises, lived in such perfect freedom and delight as in earth or heaven have never had their like.”

Mark leaned his head back on his pillow.

“And if you do not know what happened in the end…”

He closed his eyes and let the familiar words wash over him.

“…you must listen to what is told in the next chapter.”

David Hallock Sanders has had his short fiction, plays, and novel excerpts published in journals and anthologies that include Sycamore Review, The Laurel Review, Baltimore Review, 2000 Voices, The Best of Philadelphia Stories, and others. His novel-in-progress, Busara Road, was shortlisted as a finalist for the 2013 William Faulkner–William Wisdom Prize, and he is a winner of the Third Coast national fiction competition, the Benjamin Franklin Tercentenary Autobiography Project, and the Dwell/Glass House Haiku Competition.

David Hallock Sanders has had his short fiction, plays, and novel excerpts published in journals and anthologies that include Sycamore Review, The Laurel Review, Baltimore Review, 2000 Voices, The Best of Philadelphia Stories, and others. His novel-in-progress, Busara Road, was shortlisted as a finalist for the 2013 William Faulkner–William Wisdom Prize, and he is a winner of the Third Coast national fiction competition, the Benjamin Franklin Tercentenary Autobiography Project, and the Dwell/Glass House Haiku Competition.

Image credit: Greg Westfall on Flickr

Author’s photo by Nancy Brokaw

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Issue #8.

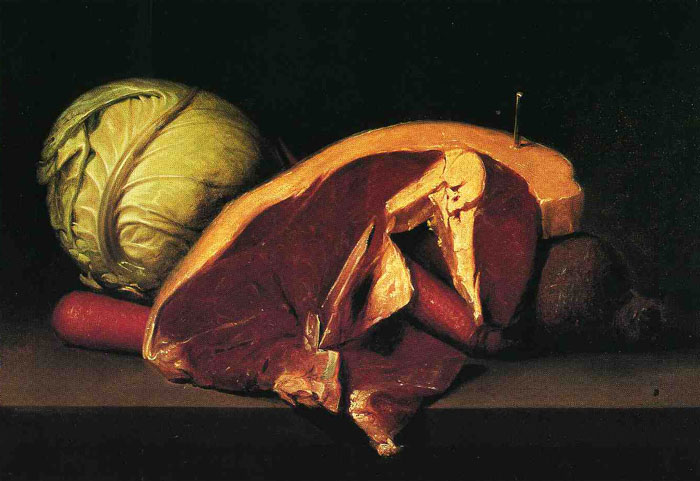

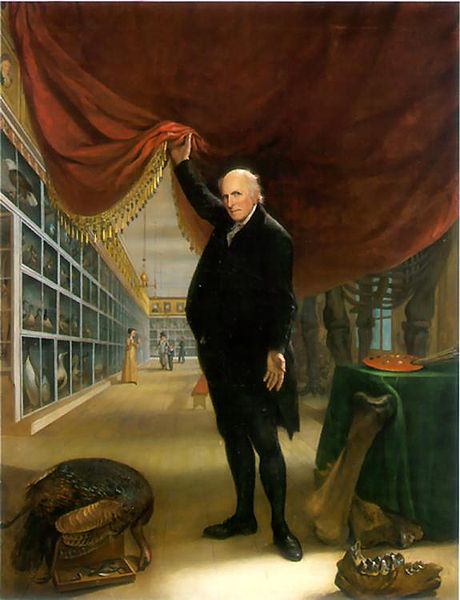

In painting, the blue sky is not only an object of its own merit, but it carries with it various symbolic meanings. Likewise, clouds, the rays of the sun—mostly invisible to us—become the life force of the landscape picture. Naturally, Birch’s nautical scenes, mere paeans to war and national feeling if not for the otherworldly clouds, come directly to mind. And so it is, yet again, the opposite when a dark background—chiaroscuro—is employed by the painter. Darkness thus becomes, exquisitely, invisible. Only the subject comes forth; only the person matters.

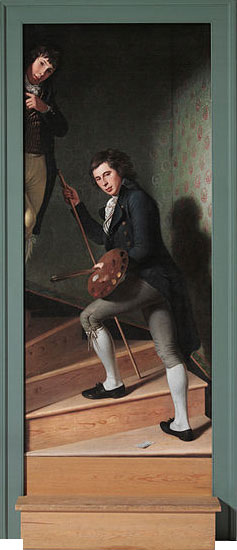

In painting, the blue sky is not only an object of its own merit, but it carries with it various symbolic meanings. Likewise, clouds, the rays of the sun—mostly invisible to us—become the life force of the landscape picture. Naturally, Birch’s nautical scenes, mere paeans to war and national feeling if not for the otherworldly clouds, come directly to mind. And so it is, yet again, the opposite when a dark background—chiaroscuro—is employed by the painter. Darkness thus becomes, exquisitely, invisible. Only the subject comes forth; only the person matters. “I think you had better ask that question of the man with the pencil,” he responded.

“I think you had better ask that question of the man with the pencil,” he responded.