Nick Greer

THUNDERBIRD

The Ojibwa call it Animikii. The Tlingit call it Shangukeidí. The Kwakwaka’wakw call it Kwankwanxwalige’, for the way it makes thunder (kʷənxʷa) lightweight (kʷəs) by pounding (ləka). No matter the tribe, its description is the same: a bird so large it creates thunder when it beats its wings. Dîné myth claims that thunderbirds live on a floating mountain Tse-an’-iska’ (“A Tall Rock Standing”). They named the thunderbird Tse-nah-ale after the fashion in which they carry men to the top of the mountain and let them fall against it: tse (“rock”) + nah (“guide”) + ajei (“heart”). The hero Nayenezgami (“slayer of alien gods”) killed the thunderbird that preyed in their lands with an arrow made of lightning. As the bird fell off its mountain, smaller birds, what we now call bald eagles, flew from its wound.

Cryptozoologists were quick to connect these myths to reports of a massive bird: a wingspan up to 5.5 meters, indigenous to the more remote forests of North America, commonly encountered during storms. The most compelling and widely circulated hypothesis is that thunderbirds are the nearly extinct descendants of Teratornis (Greek, “monster bird”) merriami, thus explaining recurring reports of young children snatched from sandboxes. Fossilized “thunderbird” skeletons found in La Brea and Woodburn often circumscribe the skeletons of lesser animals, juvenile primates being most common.

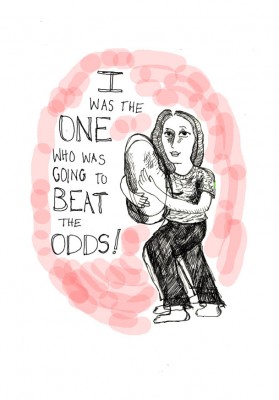

In my only encounter with a thunderbird, I was the object of such predation. I spent my childhood summers up at my family’s Sierra Nevada country house, mostly unattended while my parents hosted cocktail parties. I passed the time playing make-believe with the many pinecones and pillbugs that littered the property. During a particularly long, rainy afternoon, a great crescent shadow appeared overhead and chased me into the safety of the house’s mud room. When I was sure the bird was gone, I inched out of the doorway armed with a ski pole to discover a feather as big as my arm stuck in the sap of a tree stump. I took the feather straight to my secret hideout beneath the staircase where I kept all such treasures in a cigar box: baseball cards, invisible ink, flint arrowheads, contraband candy, a butterfly knife, a photograph of a camp girlfriend never kissed and later, tear-outs from an old Playboy, quartz and pyrite stolen from Truckee Trinkets, and finally Cannabis, sativa (Latin, “sown”) and indica (Latin, “Indian”) both.

The only other time I got close to a thunderbird was in Klukwan, Alaska, population 139 on the days Shakey wasn’t off in Sitka or Juneau, dealing smoked salmon to gourmet export companies. I was there for a summer community service trip, a punishment of sorts, for drinking half of my parent’s liquor cabinet and lying about it. Among my many jobs—babysitting kids just old enough to not need babysitting; renetting the rustbitten basketball hoops; cutting down the summer brush, vertiginous weeds like great willowherb (Chamerion angustifolium) and skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus), all so bears couldn’t sneak up on the 40 or so houses that comprised the town—my favorite was fishing. If I managed to wake up at sunrise, around 4 in the morning at that latitude, I could go out on the water with Shakey and help him pull in barbell-anchored nets that glittered with salmon, their eyes alive and dumb, continually surprised. He showed me how to kill them: either a hook through the skull or a baseball bat to the same. His was a hammerheaded aluminum bat, the same used for T-ball. I was surprised by how easy it was, to kill, but even this surprise was expected somehow. There are long histories to these motions.

Shakey kept hootch in a military-style canteen that he sipped from throughout the day, always patting the equator of his gut afterwards. By day three, I was allowed to have a sip when he did. He showed me his own treasures: the wallet full of photographs. Kids with bowl cuts and missing baby teeth, no one I’d seen among the 139. I asked if he’d ever seen a thunderbird and he shrugged. The next day after unloading the day’s haul into the smokehouse, he extracted an iodine-colored bottle from his backpack. Thunderbird, “The American Classic,” 375 mL, 17.5% ABV, bottled in Modesto, CA, not so far from my home. Its $1.99 label was half scratched off. Thunderbird is a blind, fighting drunk I’ll come to know well in the basements of old frat houses where others like me put on their facepaint and tell stories about the mythic beasts they’ve slain. ‘No,’ I said, taking the bottle anyway. ‘I meant the bird. The monster.’ I flapped my arms in a gesture that was sadly helpful. Shakey nodded and later that night he took me to the place where he and his brothers gathered. From my readings I knew it to be a widden, a special Native American landfill, the oldest of which sometimes contain fossils. I could almost make out bone beneath cigarette butts, candy wrappers, a pen knife, and the remains of countless Thunderbirds, once intact but since smashed onto the heap by Shakey and the town’s other alcoholics, now congregating around my unopened bottle just like the vultures I make them into.

After Nayenezgami killed Tse-nah-ale he found the creature’s children, roosting in a nest thatched from dead saguaros. He commanded that they sit before him and he prepared a smoke from the herbs he kept in his headdress. He puffed smoke on his fingers and drew the residues over the birds in a cross. He told them to forget their father and that his spirit would not enter them again. “The tribe called Dîné shall use your feathers. In case of famine we will eat you for meat. Whatever you say will have a double meaning: it can be taken for a lie or for the truth.”

Older now, I see why Nayenezgami killed his thunderbird with lightning. When 18th century Russian explorer Yevgeni Namag moored his boat on the shore of what he would later name Baranof Island, he didn’t expect one and then two rowboats of his well-armed men to disappear into the island’s tall coniferous forests. Instead of muskets the men on the third rowboat carried jugs of vodka and thereafter Namag found safe passage up and down the Alaskan coast. His logbook describes the natives who greeted him as red-faced men, as if this were their morphology, something to be taxonomized. But he, like all alien gods, couldn’t see it was he who was alien. It was he who made their faces red, who sent them tumbling from their perches, generations of lesser beings born from their wounds. This is the double meaning of the cryptid. We are animals both sacred and profane. A god is as easily a monster.

I am in my hideout now. I prepare a smoke and rummage through my old cigar box, its treasures intact, but changed. My thunderbird feather, once so massive, is now as small as my index finger. Hidden, it has been allowed to be special, a fetish, but revealed to the world, it loses its magic. I dip the feather in ink, no longer invisible, and bring it to the knotty pine I can only see with the flame of my Bic. There I write this, my double meaning. Should scholars later find this writing, they will mistake it for a faithful record of events, a logbook or a confession, and they will be content to know what they know. Others will recognize it as myth, but will be drunk on the wisdom this promises. And here I am: alien and red-faced, still telling stories of an animal I search for in the wilderness. Hearing thunder in the beating of a single feather.

Nick Greer is currently pursuing an MFA Creative Writing at the University of Arizona. His writing has appeared in Anamesa. He is the recipient of a Tin House Scholarship and an Academy of American Poets Prize. This summer he will be a research intern at Microsoft’s Studio 99.

Nick Greer is currently pursuing an MFA Creative Writing at the University of Arizona. His writing has appeared in Anamesa. He is the recipient of a Tin House Scholarship and an Academy of American Poets Prize. This summer he will be a research intern at Microsoft’s Studio 99.

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Issue #10.