Sarah Freligh

THE RESTAURANT AT THE END OF THE WORLD

They come from everywhere, come to us hungry. They wheel in suitcases that they park tidy under tables, drag in trash bags or carry backpacks that they ease off and set on chairs. Sometimes they bring pets—dogs and cats and once an iguana in a plaid harness—though they’re told not to. They’ll claim the damn dog just jumped into the car and wouldn’t budge, and what was I supposed to do about it anyway? We tell them we understand completely and send for the Pet Whisperer, who pulls up in her dusty grey Jeep with endearments and a pocketful of treats and sits with the owners until they’re ready to let go.

The restaurant at the end of the world never closes. We serve eggs-over-easy late at night, bowls of chili with extra spices, and pitchers of beer at daybreak. Our customers will often tell us that this is the best meal they’ve ever had, and we smile and say we’ll tell the chef. Sometimes the chef himself appears, but only after changing from his stained apron into the pressed white jacket he keeps for such occasions. They ask what was in the eggs—chives? mint?—that gives them that extra something. Sometimes they stand and shake his hand or write down a recipe and stick it away for later.

We’re taught never to ask questions—What brings you here? Where are you from?—instructed instead to listen if the customer tells us why they can’t bear to live in this world anymore. Sometimes they show us things they’ve brought from their old lives: a jeweled brooch that belonged to a wife who died of a lingering illness or a crayon drawing of the school where a couple’s six-year-old son was gunned down. There are always stories. Sometimes they ask us what it’s like at the end of the world, and we smile and tell them their slice of pie is on the house.

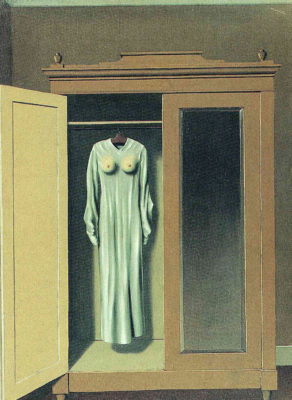

Afterward, they pay at the register, help themselves to wrapped mints or a toothpick, and take a last, long look around—at the busboy tenderly collecting glasses in a rubber tub, at the couple waving and blowing kisses into a cell phone, at the waitress unfurling a fresh linen tablecloth on a corner two-top. When it’s finally time, we point to the back of the restaurant, tell them to walk past the men’s room and the ladies’, to the red door at the end of the hallway. Goodbye, we whisper.

Hello, we say to the customers who come to us hungry.

Sarah Freligh is the author of four books, including Sad Math, winner of the 2014 Moon City Press Poetry Prize and the 2015 Whirling Prize from the University of Indianapolis, and We, published by Harbor Editions in early 2021. Recent work has appeared in the Cincinnati Review miCRo series, SmokeLong Quarterly, Wigleaf, Fractured Lit, and in the anthologies New Micro: Exceptionally Short Fiction (Norton 2018), Best Microfiction (2019-22), and Best Small Fiction 2022. Among her awards are poetry fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Saltonstall Foundation. Sarah Freligh’s flash fiction piece “The Restaurant at the End of the World” was a finalist in Cleaver’s 2022 flash contest.

Sarah Freligh is the author of four books, including Sad Math, winner of the 2014 Moon City Press Poetry Prize and the 2015 Whirling Prize from the University of Indianapolis, and We, published by Harbor Editions in early 2021. Recent work has appeared in the Cincinnati Review miCRo series, SmokeLong Quarterly, Wigleaf, Fractured Lit, and in the anthologies New Micro: Exceptionally Short Fiction (Norton 2018), Best Microfiction (2019-22), and Best Small Fiction 2022. Among her awards are poetry fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Saltonstall Foundation. Sarah Freligh’s flash fiction piece “The Restaurant at the End of the World” was a finalist in Cleaver’s 2022 flash contest.

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Issue #40.

Submit to Cleaver!