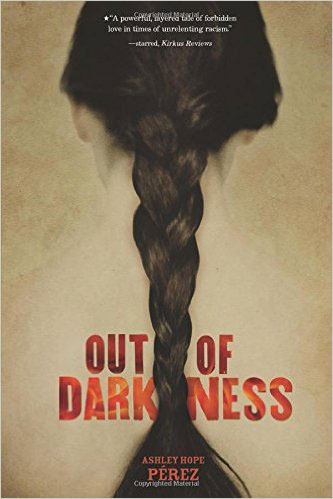

OUT OF DARKNESS

OUT OF DARKNESS

by Ashley Hope Pérez

Carolrhoda LAB, 402 pages

reviewed by Leticia Urieta

Out of Darkness is broken into parts: before the disaster and after. This compelling novel is rooted in history, and the book begins with the aftermath of the 1937 New London school explosion in East Texas and a town reeling from disaster. Volunteers move debris, collect the severed limbs of school children, and build caskets for the dead. The narrative voice embodies the horror, the grief, and the growing need for someone to blame. This is how the story begins, with a sense of impending doom, and this feeling of dread pervades the rest of the novel, the “before”, leading up to the “after.”

The story encompasses a school year, oscillating between the third person points of view of a family hoping to make a new start. Naomi Vargas moves to New London from San Antonio with her twin brother and Sister, Beto and Cari, to live with their father, her stepfather, Henry Smith. From the beginning, the rules are clear; no Spanish at school or around town; watch where you go; attend church revivals and socialize with the locals. New London is an oil town, a white town, and Naomi is immediately aware of how she doesn’t fit. Henry changes her siblings’ names to Robbie and Carrie Smith and expects her to keep his house, get to know the church wives, and learn how to cook proper southern food and biscuits, not tortillas. Each short vignette is set in one perspective at a time. And the hopes and fears of this new life are revealed.

Naomi fears living with Henry, the stepfather who has sexually abused her as a child, and being responsible for her twin siblings now that her mother, Estella, is gone. She hears Henry’s promises, the born again song and dance that he performs, but is constantly triggered by his presence. Henry is filled with self-righteousness, that this is God’s plan for his redemption from a life of drinking and sin. Beto, the sensitive, quiet twin, loves the new encyclopedias he gets to read at the new white school, and the childhood wonders of a new place, and new possibilities.

Each perspective lets the reader see the family’s story from a different angle, in brief flashes of scene that cut to the essence of each character, so that, even though the sections are short, the reader can connect to them. Each maintains its internal language patterns and embodies how each character sees themselves and others. One perspective that is infrequent, but important, is “the Gang,” representing the perspective of the teenagers of the town. They reveal the deep prejudice inherent in their upbringing, in the way they and their parents view the “Mexican Girl,” and their underlying curiosity about Naomi. All of these perspectives center around her and the book becomes largely her story.

Naomi feels isolated from the community. All the houses in the oil camp look the same and the place reeks of runoff from the derricks. Even her own brother and sister force her to become protective of her memories. They beg for her attention and seek details of their mother that Naomi wishes to keep to herself. For her, the wood by the Sabine River is her only solace. She retreats there when she is teased at school, when the grocer Mr. Turner tells her that Mexicans can’t shop in his store, or when Henry drinks and becomes explosive, threatening the relative peace they have cultivated. The woods become her sanctuary and it is in her perspective that the contrast between the woods and the town is most evident. The way she sheds her fears and sees the trees, river, and rocks where she sits as separate from the life she leads gives the reader a glimpse of her interior world.

It is here, in the woods, that she meets Wash, an industrious African American boy who lives in Egypt Town, the segregated community where the black families live. Wash, or James Washington Fuller, as his parents call him, is the son of their school’s principal. He, too, feels the heavy weight of expectation. Each job he does around town must go towards his college fund. And his parents expect that he will conduct himself properly, especially with white people, so that he will be a “credit to his race.” From the moment that Wash sees Naomi, his world is changed, and from then on, he makes it his mission to entertain and care for her siblings, teaching them to fish in the river and build things, just to get close to her. His caring, flirtatious nature draws Naomi in, and the woods become their place, where their relationship is allowed to exist beyond prying eyes. In a hollow tree, they explore their love and desire for one another, planning clandestine meetings to be alone. As their love grows, their lives become inextricably linked, and their sections are marked with “Naomi and Wash,” as their perspectives merge.

The novel lulls the reader into a false sense of hope that the story can end well for Naomi. She becomes close with some of the families in their church and is able to find a semblance of peace in the secluded nature of her romance with Wash. Their growing love engulfs and protects them from the prejudices and intrusions of a town bent on tearing them a part.

This hope is punctured again and again by Naomi’s setbacks. She lives with the fear of Henry’s advances as he decides that he would like to take her for a wife, the weight of preserving the memory of her mother to the twins who never knew her, and having to find her place in an East Texas oil town where she is unwanted, unable to merge with the African American community and pushed away from the white majority because of her Mexican ethnicity. As her fear of Henry grows, she and Wash devise a plan to leave the strictures of a society tying them down, to take the twins and go where no one can follow. With each dip into misfortune, the reader is reminded that the story can only end one way, in disaster.

After the school explosion from a gas leak, Naomi and Wash must confront the horrors of grief and a town on the rampage, itching for someone to blame. Wash makes a convenient target, a young black man who, as the white men of the town see it, has invaded the white spaces, doing odd jobs around the school and being seen with the Smith children. The vitriol of their attacks fills one with dread until the end.

This is a story that, while fictional, reflects the heritage of a time in our collective histories that many would like to forget, when racism, hatred and violence were natural pieces woven into the fabric of the American South. The ending is traumatic, and the book in general could be considered triggering to those who have experienced extreme violence or rape. One could make a case that the ending is too violent, too unbelievable for modern readers to relate to, and therefore the rest of the book loses its merit because in the end there is no hope. Yet, when reading the recent news that twelve year old Tamir Rice, gunned down in a park as he played, will receive no justice, that no one will be held accountable for his death, and that the people whose job it is to see that justice is done spent more time criminalizing him than the police who murdered him, this novel, set eighty years ago, does not seem like fiction. Though the characters are part of the author’s imagination, they reflect the best and worst of people and how they come together or are driven apart by tragedy.

In the epilogue, an adult Beto decides that he must tell the true story of what happened in the year his family lived in New London, and how they lost everything, including the right to represent themselves truthfully. In a rare authorial intrusion, the author pleads with the audience: “He needs you reader. All he asks is that you take the story up and carry it for a while.” It is a story that stays with you, and, as much as the reader would like to return to the seclusion of Naomi’s woods and the hollow tree where the ugliness of life cannot intrude, it leaves a heaviness inside you that is not easily shed. We have seen the consequences of blocking out the darkness and leaving these stories untold. With this novel, Ashley Hope Pérez attempts to bring those stories to light.

Leticia Urieta is a Tejana writer from Austin, TX. She is a graduate of Agnes Scott College and is a fiction candidate in the MFA program at Texas State University. She won Agnes Scott’s Academy of American Poet’s prize in 2009 and her work has appeared in Cleaver, the 2016 Texas Poetry Calendar, and Blackheart. Leticia lives in Austin, Texas with her husband and two dogs. She is using her love of Texas history and passion for research to write a historical novel about the role of Mexican soldaderas in Texas’ war with Mexico.

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Book Reviews.