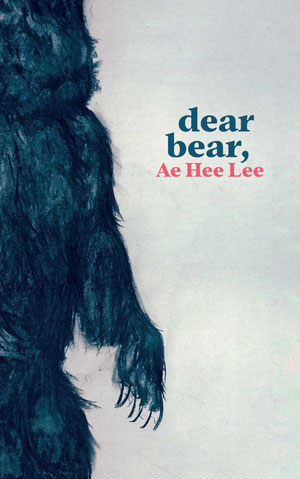

DEAR BEAR

by Ae Hee Lee

Platypus Press, 42 pages

Reviewed by Juniper Jordan Cruz

Dear Bear begins with the gripping dedication, “For Daniel, to the end,” and from there, takes its readers to the end of the world it introduces. This is author Ae Hee Lee’s world that exists in a collection of letters addressed to the titular Bear—who is both a real and parabolic bear.

Dear Bear begins with the gripping dedication, “For Daniel, to the end,” and from there, takes its readers to the end of the world it introduces. This is author Ae Hee Lee’s world that exists in a collection of letters addressed to the titular Bear—who is both a real and parabolic bear.

The book is set in a forest, “at the border of every ruin, of every past home.” The forest is also both real and parabolic as a form of borderland, acting as a Romantic landscape: sublime and shaped around the speaker’s psyche. Because of this, the forest becomes a vessel for the speaker’s exploration of the relationship between her and Bear. Ae Hee Lee establishes the forest as a post-apocalyptic setting to navigate both the relief and anxiety that comes from surviving an old world and entering a new one. In this case, Lee’s ‘Dear Bear’ speaks on the annihilation of an old life that comes with falling into new love. The “crossover from one to two” simultaneously contends with its own borderland: the end of two singular people and the beginning of a couple, the end of a world into the beginning of the next.

Lee does not shy away from the paradox of a relationship showing the self in the other, rather, she uses her epistolary poems to show clashing identities and clashing tones at play in the same moments. In the book’s first poem titled [Dear bear,] we see this example,

Dear bear,

I’m writing these letters in the innermost layer of your heart. You’ll never escape them. Having written them myself, I won’t survive them either.

Sincerely,

The poem’s tone moves from sentimental to dangerous. This is a technique well-utilized by Ae Hee Lee, giving the reader no sense of peace, no room for settling, and, like Bear, for the reader, there is no way to escape.

Lee strays away from the normal valedictions found in letters, moving from typical “sincerely,” to “with longing,” “whole,” “untaking,” and “open.” Considering valedictions as displays of the relation between the sender and receiver of a message, the reader can begin to recognize that Lee embraces them as a new form, another border for her poetry to balance on. Using these sign-offs in unexpected ways with atypical phrasing allows Ae Hee Lee to signal the fluctuations and endurance of the larger relationship ‘Dear Bear’ details.

At its height, the use of letters as form for each poem in this collection provides a sense of voyeurism, giving the sensation that we as readers are becoming intimate with information clearly not addressed to us. As if we, as the readers, are not meant to be reading these letters. Because of this, the speaker can be vulnerable and divulge secrets only known between her and Bear such as his “fetish for small feet,” and intense moments of vulnerability such as,

How is it you say you prefer me naked after all I’ve done, after all everyone has taught me to do? I stop my twirling, my twisting. I don’t know whether to cry or laugh.

Still, when Lee is not letting us into a brief, yet potent moment of intimacy that fits incredibly well these letter-poem hybrids, the poems loosely invoke the epistolary tradition’s religious roots. Still, they are less didactic and more meditative– more constructing of the self than of a larger narrative, musing on the ecology of the forest to explore and explain Lee’s feelings of partnership. There is a loose motif of religious imagery that is weaved throughout this book that seems out of place until we find its origin in the narrator’s first-ever meeting with Bear where she

Used to go to church wearing heels, I would hide those little leather cages in the garbage can the moment I got back into the house– I would trace the arch of my foot with my pinky, paint dandelions on my soles. Then, I met you, remember?

This moment, which is one of the most grounded in reality throughout the entire book, roots the speaker in her origin: being from outside the forest. She is a stranger of this curious land. Using the form of the epistle throughout each poem, she gives us insight into the borders of her own language in which this new world and new self-being constructed throughout this book, can only be explained through the lens of the speaker’s old self.

These limits shape the tension of this book: the speaker’s somewhat inevitable annihilation into the forest. It also serves as a reason why this book exists. The speaker complains that the forest does not have ears for her to, “nibble, hiss– drip my words into the hollow.” She goes on to compare the writing of the forest as making a diorama of it as “pretending to leave.” She does this “To keep myself [The speaker] away from the forest, to practice separation. Independence. I would lose myself otherwise.” This looming end carries the reader through each pungent poem, admiring the gorgeous piece of the forest’s ecology while watching it slowly consume Lee; as each flora that Lee admires in one poem devours her body in the next.

Ae Hee Lee takes great care in circling back to some of the most emotionally charged images within the book. Or rather, the images come back to overwhelm her. For example, the camellia who, “Whirls with the voiceless music of planets,” returns to be an agent in the dissolving of her body. Even when so many parts of the forest have contributed to some form of annihilation of the speaker, she still begs for more annihilation from one of the forest’s inhabitants: Bear. She becomes a fish and begs for Bear to chase her down the river. This moment harkens back to our first introduction to Bear in the book where the speaker claims that Bear was looking at as if she were a fish in a river.

Like the flora and fauna of the forest, the metaphors Lee makes of them overwhelm you, only to return to their roots when you are completely consumed by them later in the book. Because of this, Dear Bear becomes a collection of forty short poems that is best read twice: once to let yourself be consumed by the indulgent and palpable imagery of the forest until you find itself at its roots, and after you know the roots of the forest (and the speaker), again to witness how Lee constructs the self through her own annihilation.

Cleaver Poetry Reviews Editor Juniper Jordan Cruz is a writer and body artist from Hartford, Connecticut. She is a 2019 graduate from Kenyon College, where she studied creative writing. Her work has been published in Poets.org, Lambda Literary, and the Atlantic. Her works have also been recognized by Gigantic Sequins and the Academy of American Poetry Prize at Kenyon College. Email to query Juniper about poetry book reviews.

Cleaver Poetry Reviews Editor Juniper Jordan Cruz is a writer and body artist from Hartford, Connecticut. She is a 2019 graduate from Kenyon College, where she studied creative writing. Her work has been published in Poets.org, Lambda Literary, and the Atlantic. Her works have also been recognized by Gigantic Sequins and the Academy of American Poetry Prize at Kenyon College. Email to query Juniper about poetry book reviews.

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Book Reviews.