Kate Spitzmiller

THE SONG OF SAINT GEORGE

“But Martin was born in Lancashire,” I said to the man seated across from me the afternoon of the arrest.

The man, whose black hair was slicked neatly back, offered me a cigarette.

I declined. “Martin’s not German, much less a German spy.”

The man placed a cigarette between his lips and lit it with the flick of a silver lighter. He inhaled deeply and then exhaled, the smoke blue-grey in the dimly-lit room.

“Mrs. Ridley,” he said. “We have ample evidence of your husband’s activities in support of the Third Reich.”

“That’s ludicrous!”

“Madam, I assure you, everything is in order.”

“Martin teaches Medieval Literature at Oxford. He spends his time grading papers, not spying.”

The man tapped his cigarette over the black ashtray at the center of the table. Ash dropped soundlessly.

“Has Martin ever been to Germany?”

I blinked. “Of course. Before the war. For research.”

“And he speaks German?”

“No. I don’t think so.”

“Then how does he conduct his research?”

“He reads. He can read all the variants of Medieval German. But that’s not the same thing as being able to speak modern German. It doesn’t make him a spy. It makes him a scholar.”

The man exhaled smoke. It drifted lazily up toward the ceiling, captured by the pale light of the single bare bulb that illuminated the room.

“Sir, if I could speak with your superior, we could clear this matter up quite quickly.”

He ignored me. “How long have you been married?”

“Three years in March.”

“How long did you know each other before you were married?”

“Six months.”

“That’s not long.”

I blushed.

The man leaned forward. “I’m not here to make you feel uncomfortable, Mrs. Ridley. Quite the opposite. It is often difficult for the spouses to accept reality.”

“Reality?”

“The reality that they have been living their lives as normal, and all the while the person buttering their toast on the other side of the kitchen table is working for Hitler.”

“Martin doesn’t work for Hitler.”

“A common response.” The man tapped his ash again.

“Perhaps your superior—”

“I am the superior in this case, Mrs. Ridley.”

“Well, then, perhaps I could have your name.”

“You may call me Mr. Brown.”

“Mr. Brown, there has been some horrible mistake—”

“When was the last time your husband visited Germany?”

“I told you, before the war.”

“When?”

“1938, I think.”

“What month?”

“During the school holidays,” I said. “July or August.”

“And you didn’t travel with him?”

“No. It was a research trip. He planned to be in libraries the entire time. I would have been bored.”

“Did he say you would be bored, or did you decide you would be bored?”

“I don’t recall. And I resent the implication—”

“What was he working on?”

“He specializes in lyric poetry. There was a poem about Saint George he was hoping to re-translate.”

“Das Georgslied.”

“Excuse me?”

“Das Georgslied. Or the Song of Saint George. Written in Old High German. 1000 A.D.”

“Yes, that sounds right.”

“Saint George. Patron saint of England.”

“Yes.”

Mr. Brown crushed his cigarette in the ashtray. The filter collapsed like an accordion. “Do you know what a book cipher is, Mrs. Ridley?”

“No, I can’t say that I do.”

Mr. Brown’s thin lips twitched upward in what I imagined passed for a smile in his world. “A book cipher,” he said, “is a way of sending coded messages using a preexisting text as the code-book.” The lips twitched again. “And your husband’s German handler seems to have a sense of humor. Or at least a sense of irony.”

“I don’t understand.”

“The Song of Saint George. Meant as a poke in the eye to Churchill, I’d imagine.”

“It’s just a poem.”

“Not in your husband’s hands.” Mr. Brown opened the blue folder beside him. “Twelve coded messages. All sent from the postbox outside the Knight’s Inn pub in Oxford. All in your husband’s handwriting.”

He passed me a sheet of paper. The writing was unmistakably Martin’s—the curl at the end of the f, the little tail on the t. But the writing was incomprehensible. Letters, but also numbers.

“Nonsense, right?” Mr. Brown said.

I nodded, still staring at the mess of letters and numbers. Martin’s mess of letters and numbers.

“It’s nonsense,” Mr. Brown said, “until you use the Song of Saint George to decipher the code. Then it tells you how many bombers flew east from RAF Abingdon on each evening last week, and how many came back.”

My chest tightened.

“How close do you live to Abingdon?”

“We live just down the road. On Boar’s Hill. Martin…”

“Martin, what?”

“Martin…walks the dog to Abingdon every evening. He says he likes to watch the planes…”

Mr. Brown picked up the sheet of paper and slid it back into the folder. “He does like to watch the planes, Mrs. Ridley. Quite a lot.”

Kate Spitzmiller writes historical fiction from a woman’s perspective. She is a flash fiction award-winner, with two pieces published in the anthology Approaching Footsteps. Her flash piece “Brigida” has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Kate Spitzmiller’s debut novel, Companion of the Ash, is set for release in 2018 by Spider Road Press. She lives in Massachusetts where she tutors junior-level hockey players as her day job. You can visit Kate Spitzmiller’s blog at www.katespitzmiller.com.

Kate Spitzmiller writes historical fiction from a woman’s perspective. She is a flash fiction award-winner, with two pieces published in the anthology Approaching Footsteps. Her flash piece “Brigida” has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Kate Spitzmiller’s debut novel, Companion of the Ash, is set for release in 2018 by Spider Road Press. She lives in Massachusetts where she tutors junior-level hockey players as her day job. You can visit Kate Spitzmiller’s blog at www.katespitzmiller.com.

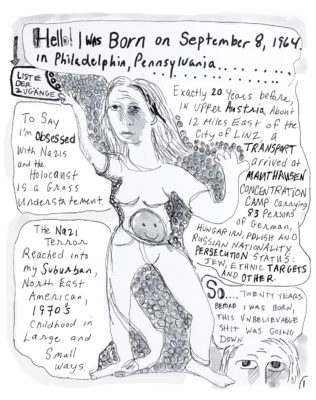

Image: Saint George Killing the Dragon, detail. Bernat Martorell, 1430-1430, Art Institute of Chicago

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Issue #20.