Kelly McQuain

THE EMPATHY MACHINE: A Visual Narrative on the Poetics of Kenneth Goldsmith

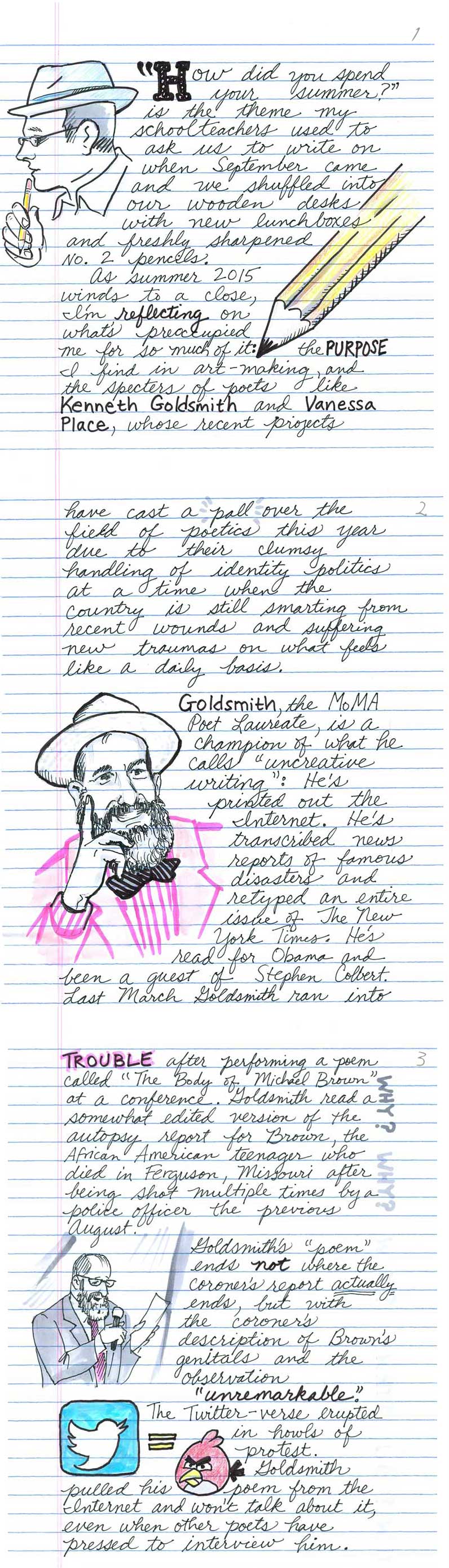

“How did you spend your summer?” is the theme my schoolteachers used to ask us to write on when September came and we shuffled into our wooden desks with new lunchboxes and freshly sharpened No. 2 pencils.

As summer 2015 winds to a close, I’m reflecting on the what’s preoccupied me for so much of it: the purpose I find in art making, and the specters of poets like Kenneth Goldsmith and Vanessa Place, whose recent projects have cast a pall over the field of poetics this year due to their clumsy handling of identity politics—at a time when the country is still smarting from recent wounds and suffering new traumas on what feels like a daily basis.

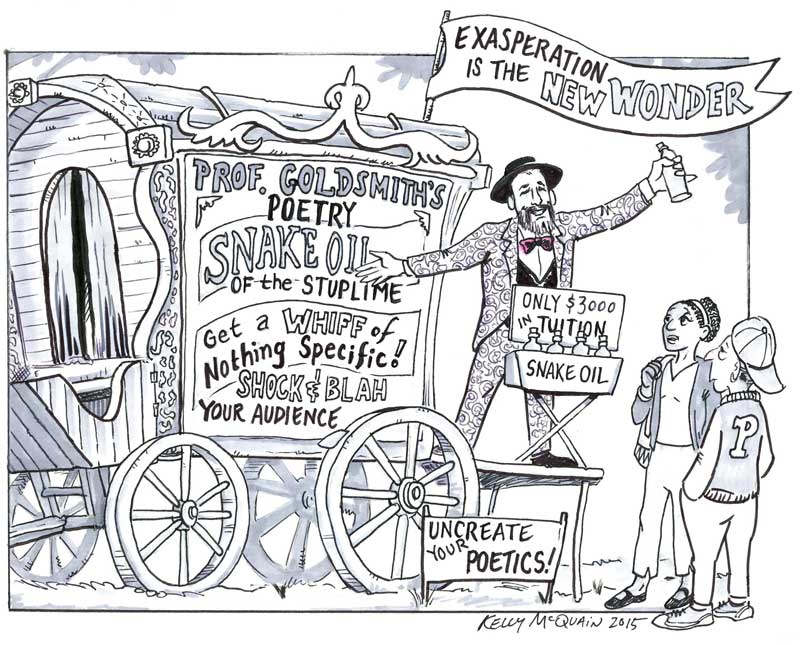

Goldsmith, the MoMA Poet Laureate, is a champion of what he calls “uncreative writing.” He’s printed out the Internet. He’s transcribed news reports of famous disasters and retyped an entire issue of The New York Times. He’s read for Obama and been a guest of Stephen Colbert.

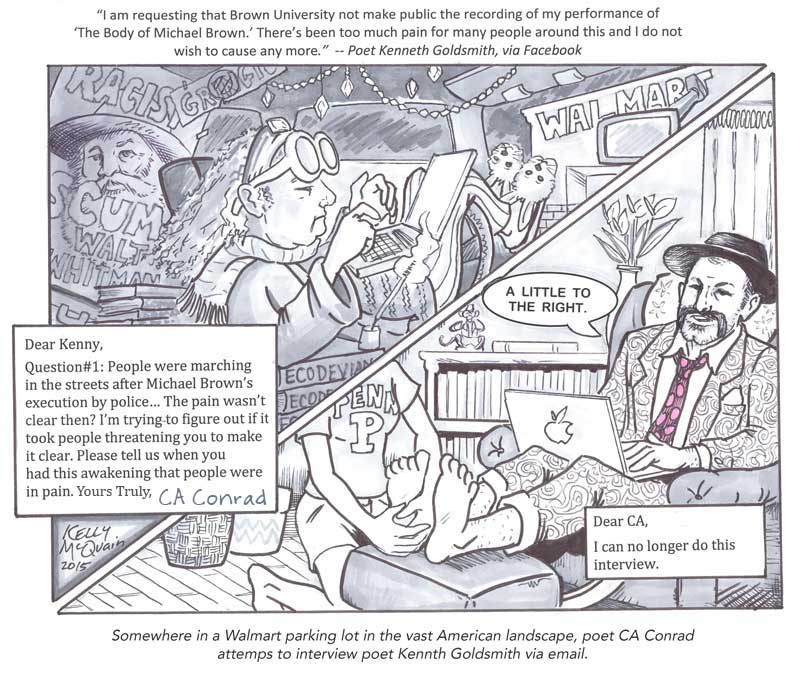

Last March Goldsmith ran into trouble after performing a poem called “The Body of Michael Brown” at a conference. Goldsmith read a somewhat edited version of the autopsy report for Brown, the African American teenager who died in Ferguson, Missouri, after being shot multiple times by a police officer the previous August.

Goldsmith’s “poem” ends not where the coroner’s report actually ends, but with the coroner’s description of Brown’s genitals and the observation “unremarkable.” The Twitter-verse erupted in howls of protest. Goldsmith pulled his poem from the Internet and won’t talk about it, even when other poets have pressed to interview him.

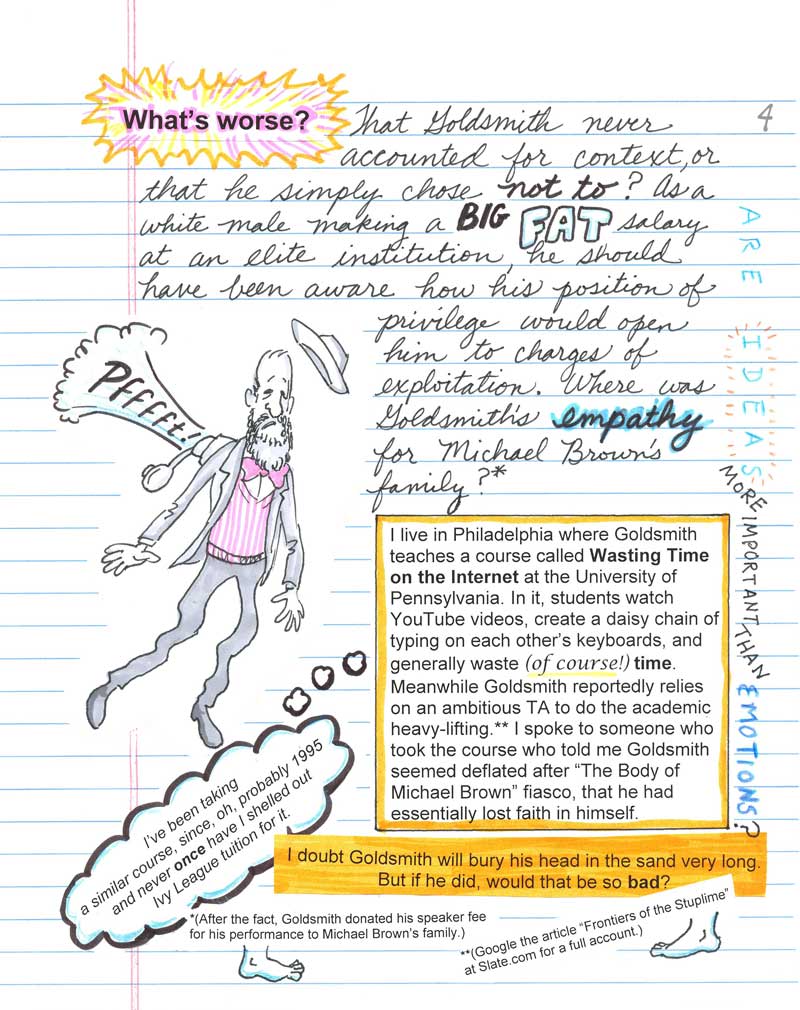

What’s worse? That Goldsmith never accounted for context, or that he simply chose not to?

As a white male making a big fat salary at an elite institution, he should have been aware of how his position of privilege would open him to charges of exploitation. Where was Goldsmith’s empathy for Michael Brown’s family?*

I live in Philadelphia, where Goldsmith teaches a course called “Wasting Time on the Internet” at the University of Pennsylvania. In it, students watch YouTube videos, create a daisy chain of typing on each other’s keyboards, and generally waste time (of course!). Meanwhile Goldsmith reportedly relies on an ambitious TA to do the academic heavy-lifting.**

I spoke to someone who took the course who told me Goldsmith seemed deflated after the “Body of Michael Brown” fiasco, that he had essentially lost faith in himself.

I doubt Goldsmith will bury his head in the sand very long. But if he did, would that be so bad?

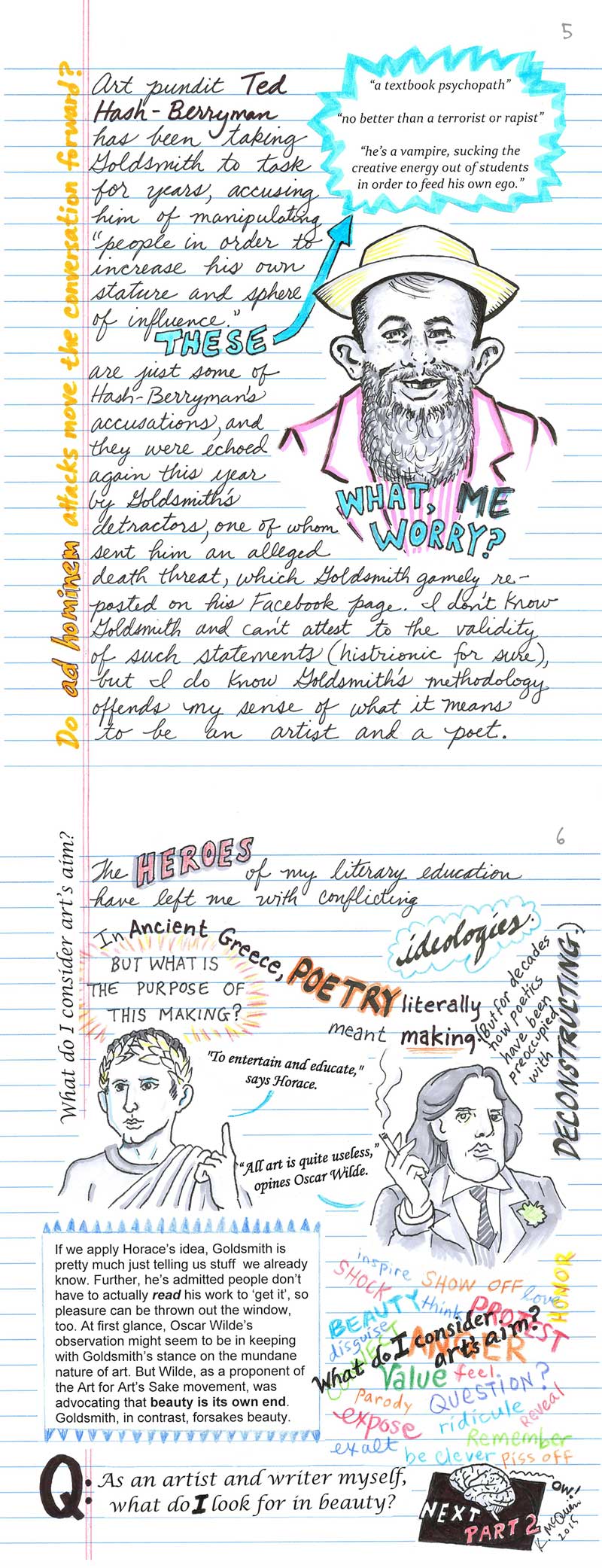

Art pundit Ted Hash-Berryman has been taking Goldsmith to task for years, accusing him of manipulating people “in order to increase his own stature and sphere of influence.”

“a textbook psychopath”

“no better than a terrorist or rapist”

“He’s a vampire, sucking the creative energy out of his students in order to feed his own ego.”

Do ad hominem attacks move the conversation forward? These are just some of Hash-Berryman’s accusations, and they were echoed again this year by Goldsmith’s detractors, one of whom allegedly sent him a death threat, which Goldsmith gamely reposted on his Facebook page. I don’t know Goldsmith and can’t attest to the validity of such statements (histrionic, for sure), but I do know Goldsmith’s methodology offends my sense of what it means to be an artist and a poet.

What do I consider art’s aim?

The heroes of my literary education have left me with conflicting ideologies. In ancient Greece, poetry literally meant “making.” But for decades now, poetics have been preoccupied with deconstructing. What is the purpose of making?

“To entertain and educate,” says Horace.

“All art is quite useless,” opines Oscar Wilde.

If we apply Horace’s idea, Goldsmith is pretty much just telling us stuff we already know. Further, he’s admitted that people don’t have to actually read his work to “get it,” so pleasure can be thrown out the window, too. At first glance, Oscar Wilde’s observation might seem to be in keeping with Goldsmith’s stance on the mundane nature of art. But Wilde, as a proponent of the Art for Art’s Sake movement, was advocating that beauty is its own end. Goldsmith, in contrast, forsakes beauty.

As a writer and artist myself, what do I look for in beauty? Stay tuned for Part 2, coming in Cleaver’s Issue 13, March 2015!

*After the fact, Goldsmith donated his speaker fee for his performance to Michael Brown’s family.

**Read “Frontiers of the Stuplime” by Katy Waldman on Slate.com for a full account.

Kelly McQuain spent summer 2015 as a Lambda Literary Fellow in Los Angeles and as a Tennessee Williams Scholar at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference in Tennessee. His chapbook, Velvet Rodeo, won the BLOOM Poetry Chapbook Prize and two Rainbow Award citations. His poetry and fiction have appeared in The Pinch, Eleven Eleven, Painted Bride Quarterly, Philadelphia Stories, and numerous anthologies: Drawn to Marvel: Poems from the Comic Books; Rabbit Ears: TV Poems; Best American Erotica; Men on Men; and Skin & Ink. Kelly McQuain has twice held fellowships from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts. McQuain used to illustrate sexy superhero comics but now works as a writing professor in Philadelphia. His book reviews and essays on city life appear from time to time in The Philadelphia Inquirer. Learn more at his website. Read Kelly McQuain’s poem “Jam” in Issue No. 1 of Cleaver.

Kelly McQuain spent summer 2015 as a Lambda Literary Fellow in Los Angeles and as a Tennessee Williams Scholar at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference in Tennessee. His chapbook, Velvet Rodeo, won the BLOOM Poetry Chapbook Prize and two Rainbow Award citations. His poetry and fiction have appeared in The Pinch, Eleven Eleven, Painted Bride Quarterly, Philadelphia Stories, and numerous anthologies: Drawn to Marvel: Poems from the Comic Books; Rabbit Ears: TV Poems; Best American Erotica; Men on Men; and Skin & Ink. Kelly McQuain has twice held fellowships from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts. McQuain used to illustrate sexy superhero comics but now works as a writing professor in Philadelphia. His book reviews and essays on city life appear from time to time in The Philadelphia Inquirer. Learn more at his website. Read Kelly McQuain’s poem “Jam” in Issue No. 1 of Cleaver.

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Issue #11.