David Novack and Andrei Malaev-Babel (Odessa Films), Introduction by David Novack and Dylan Hansen-Fliedner

FINDING BABEL: Fiction and Non-fiction Blend in Documentary Film

“What happened on May 15, 1939?” we asked Antonina Pirozhkova in a 2003 interview, a few short years before her death. She sat uncomfortably still, staring off camera as if gazing into the painful, not-so-distant past, remembering her late husband, Isaac Babel.

“I can’t go through it. Not again.”

That question had haunted Pirozhkova for sixty-four years. The silence and the emotion we captured in her face that day started a twelve-year journey to bring Isaac Babel’s story to life as a documentary film.

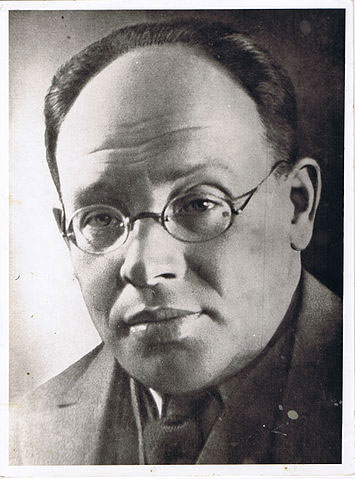

Isaac Babel is considered one of the most significant literary figures of the early Soviet Union. A writer, translator, and journalist, he began publishing shortly after the revolution of 1917 with the help of his mentor, Maxim Gorky. The older author advised the young writer to go and see the world, incorporating what he saw into his fiction. Babel signed up with the Red Army in the Soviet-Polish Civil War as a war correspondent and began keeping what would become his 1920 Diary. Only twenty-six years old, Isaac Babel developed a unique literary practice rooted in the act of witnessing.

As a documentarian, Babel captured reality, filtering and distilling it into memorable impressions in his diary. These observations and reports would later be transformed into a collection of short stories, Red Cavalry, which blend fact and fiction into powerful narratives. Red Cavalry thrust Babel upon the international stage.

In these stories, Babel wrote under the alter ego Kyril Lyutov, who, like Babel, hides the fact that he is Jewish from his fellow Cossacks (who were widely known for their antisemitism). The intertwining of fact and fiction and the semi-autobiographical meditation on identity became fertile ground for developing a formal and stylistic approach for our film, Finding Babel. With this in mind, we looked even more deeply at Babel’s approach to literature.

Isaac Babel said of his short stories that he wanted to do in five pages what took Tolstoy five hundred. He was interested in essences and in ambiguities, certainly not the ideal propagandist for the USSR. His stories often had an ethereal, otherworldly dimension and he was not afraid to show brutality as alternately heroic and terrible. His process involved taking in the world around him and condensing it through the lens of a protagonist with an ambiguous relationship to the events around him. This is how Babel saw human nature.

Similarly, the film Finding Babel condenses a twelve-year investigation and over 350 hours of footage into a two-hour film that explores impressions of history, sometimes glorious and other times brutal, rooted in the emotional experience of a witness. The sculpting and refining of Finding Babel called for a blend of vérité encounters throughout Ukraine, France, and Russia interspersed with animated treatments of Babel’s fiction and archival treatments of his diary as well as sit-down interviews along the way.

Finding Babel follows the late author’s grandson, Andrei Malaev-Babel, on a journey to some of the places upon which his grandfather left an indelible mark. Andrei’s grandmother was Antonina Pirozhkova, whose 2003 interview planted the seeds for our film and whose passing in 2010 (at the age of 101) inspired Andrei’s journey. After sharing his family history in the United States and hearing from scholars like Carol Avins (editor of the U.S. edition of Babel’s 1920 Diary), and Val Vinokaur (translator of a new edition of Babel’s work), Andrei sets off for Western Ukraine, the battleground upon which Red Cavalry took place.

Our experience of the landscape and the people of L’viv, Brody, and Kozin brought out the profound resonances and continuity of Isaac Babel’s work. We include excerpts from Babel’s stories and his diary interspersed with Andrei’s exploration. The twin poles of fact and fiction call for different visual treatments. When relevant fragments of Babel’s short stories take us along Andrei’s search, Babel’s words are juxtaposed against our live footage, transformed into evocative blended animation. In instances where we present excerpts from the 1920 Diary, archival footage gives a more grounded sense of historical representation and continuity.

This leg of our trip also forced us to confront historical realities that still haunt the lands of Western Ukraine in surprising ways. Indeed, we felt immersed in a kind of witnessing of our own. In this beautiful but troubled countryside, past meets present as real and imagined spaces collide and overlap in both Babel’s fiction and the experience of making the film. Honoring this confluence of literary modes and personal experience became paramount to the structure and mood of Finding Babel.

Babel did not limit his writing to soldiers of the Red Army; his other set of major works focused on his hometown of Odessa, Ukraine. As in Red Cavalry, self-mythology is present in these works of fiction. The Story of My Dovecot is a semi-autobiographical tale centered on the bloody Odessa Pogrom of 1905, immortalized in Sergei Eisenstein’s masterpiece film, Battleship Potemkin. A larger sequence of stories called the Odessa Tales focuses mainly on the area’s Jewish gangsters, ruled by Benya Krik, “The King.” These tales, like Babel’s other work, oscillate between a reverence for his brutish thugs and a fear of them. The narrative offers complex perspectives on corruption and power structures.

In Finding Babel, we incorporate footage from a 1926 film adaptation of the Odessa Tales in our animation treatment of the stories; clips from the film are superimposed over footage of the Moldovanka neighborhood near Babel’s childhood home and where the stories take place. With this visual treatment, “The King” occupies an ironic space in today’s Odessa, as does a newly installed statue of Babel, in a culture that has yet to look squarely at its past. The statue raises questions of the discrepancy between his heroic reception today and his vilification in the years leading up to his death.

As Babel began publishing his work, he received international acclaim, traveling abroad to Paris to visit his first wife and young daughter and to act as a representative of the young Soviet Union. He was celebrated as a hero, living in relative privilege compared to much of the impoverished Soviet population. But the political climate changed with Stalin’s rise to power and, with it, so did Babel’s standing. His work increasingly clashed with the state-enforced “socialist realism” and thus became unpublishable. His play Maria was shut down during rehearsals in 1935 by NKVD agents and was not performed in Russia until the end of the Soviet Union. For the film, we begin the trajectory toward Babel’s execution in Paris with excerpts from Maria, a work that is fundamentally about betrayal—by family, by society, by ideals.

In the summer of 1935 at a conference in Paris—often considered to be Babel’s last hope of escaping his fate—Babel announced he was becoming a master of the new literary genre of “silence,” and returned to Moscow. Babel’s very subtle blend of satire was tolerated for a time, but by 1939, after a long period of silence in which he wrote furiously but published no work, Stalin’s tolerance of the writer “with spectacles on his nose and autumn in his heart” had run out. He was arrested in the middle of the night at his country home in Peredelkino, a private community built for Soviet writers in 1934. The NKVD agents brought his second wife, Antonina Pirozhkova, with them from Moscow. As he was escorted through the gates of Lubyanka Prison, he turned to her and said, “Someday we’ll see each other…”

They never did.

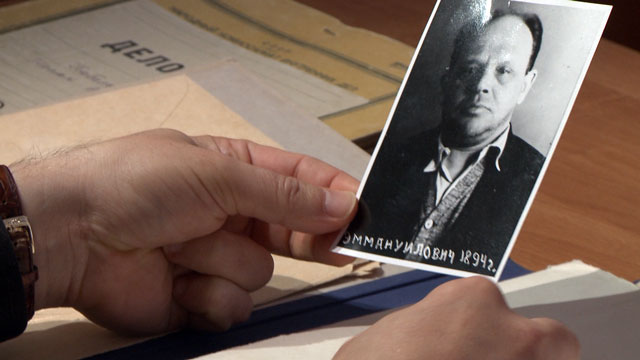

Upon his arrest in 1939, an unpublished body of work was taken from Babel’s home, now lost in an enigmatic paper trail. Some accounts say it was burned. Others say it may still be buried deep in an archive or even a private collection. The truth eludes us as it eluded Antonina Pirozhkova. For fifteen years, she was fed false accounts from NKVD agents that Babel was living and working in a camp in Siberia. What she didn’t know, and didn’t find out until after his rehabilitation in 1956, was that Babel had been shot in his cell in Butyrka Prison on January 27, 1940, after a shockingly brief trial the day before. Up to the end, he pleaded to be allowed to finish his writing.

As the first American film crew ever allowed inside the KGB archives, we did not come any closer to finding these potential masterpieces. We were graced with unprecedented access to Babel’s case file and an ample amount of time to review it. When the question of the missing manuscripts was raised, the chief archivist, clad in bureaucratic gray, told Andrei with a shrug and a droll sigh that the file pointing to their whereabouts was missing or never existed. Yet, a discovery was still made that day. Chillingly confronting his grandfather’s case file, Andrei found his grandfather’s last act of writing. It was not a lost manuscript nor a personal letter, but rather a somewhat shaky signature officially acknowledging his own death sentence.

Seventy-five years after Babel’s execution, we are left with what Gregory Freidin refers to as The Enigma of Isaac Babel. The blend of fact and fiction in Babel’s work shrouds him in self-mythology. The political situation he found himself in resulted in an unfortunate silence in the years leading up to his execution. Babel is a man of many seemingly irreconcilable mysteries. His story is still being written.

Literary projects often evolve on their own schedule, not conforming to the pressures and deadlines of an author, publisher, or film director. They have the capacity to gain a very special significance given the right circumstances. Twelve years after filming Pirozhkova’s honest and heart-wrenching interview and seventy-five years after Babel’s unceremonious execution, it is no coincidence that the time for Babel’s writing has come again.

Andrei’s search for his grandfather leads us to many startling situations that remind us of the need to witness in these particularly turbulent times. In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack, Bloomberg News drew a connection to the executions of Isaac Babel and other Soviet intellectuals and artists. Pussy Riot and Ai Weiwei face censorship and oppression in Russia and China (and those are just the publicized cases).

Echoes of the conflict Isaac Babel chronicled in his 1920 Diary have appeared in the last year as conflict erupted among Russian separatists and Ukrainian nationalists. Isaac Babel’s work and life are a call to witness and to report, contextualizing harsh truths in the complexities of humanity. Our search for Babel shows that although the man may have been executed, his work still resonates powerfully.

David Novack wrote, produced and directed the IDA Pare Lorentz award-winning documentary Burning the Future: Coal in America (2008), which has screened theatrically and on The Sundance Channel. He has been a producer, post supervisor, and associate producer for many films and television series, including Kimjongilia (2009 Sundance Official Selection). He has a Bachelor of Science in engineering from the University of Pennsylvania, and a degree in music from Berklee College of Music. He is a professor of film at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design and the director/producer/writer of Finding Babel (2015).

David Novack wrote, produced and directed the IDA Pare Lorentz award-winning documentary Burning the Future: Coal in America (2008), which has screened theatrically and on The Sundance Channel. He has been a producer, post supervisor, and associate producer for many films and television series, including Kimjongilia (2009 Sundance Official Selection). He has a Bachelor of Science in engineering from the University of Pennsylvania, and a degree in music from Berklee College of Music. He is a professor of film at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design and the director/producer/writer of Finding Babel (2015).

Dylan Hansen-Fliedner is a Brooklyn-based filmmaker and poet. He has a B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania in cinema studies and English, with Honors in creative writing. His poetry has been published by Gauss PDF and 89plus/LUMA Foundation and has been featured in The Atlantic. He is the co-director of the feature film Driving Not Knowing (2015) and co-editor and associate producer of Finding Babel (2015).

Dylan Hansen-Fliedner is a Brooklyn-based filmmaker and poet. He has a B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania in cinema studies and English, with Honors in creative writing. His poetry has been published by Gauss PDF and 89plus/LUMA Foundation and has been featured in The Atlantic. He is the co-director of the feature film Driving Not Knowing (2015) and co-editor and associate producer of Finding Babel (2015).

Find out more at FindingBabel.com or facebook.com/FindingBabelDoc

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Issue #9.