Debra Fox

RICOCHET

October 27, 2018 9:07 a.m., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Twenty-one-year-old Matthew clicks his tongue in time to each step he takes. Tramping on carpet, he still makes the cupboards rattle as he descends the staircase into the living room. Knowing the clicking signifies contentment, his mother turns over in her bed and allows herself fifteen more minutes of sleep.

It’s the weekend, so Matthew has gotten himself dressed. He’s put his shirt on backwards and his shoes on the wrong feet. He plonks down next to the bookcase where his picture books are lined up. He removes one book at a time, rubbing each glossy page between his thumb and forefinger, and places it next to him, building a neat tower. Matthew is humming Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, probably inspired by Goodnight Moon, one of his favorite books. Or at least that’s what his mother hypothesizes as she lies in bed half-asleep, listening to him. She can’t know for sure since Matthew is severely autistic and non-verbal.

What she does know is that this sort of repetitive activity centers him, and enables him to block out competing sounds, colors and stimuli all vying equally for his attention.

◊

October 27, 2018 9:40 a.m., Squirrel Hill, Pennsylvania

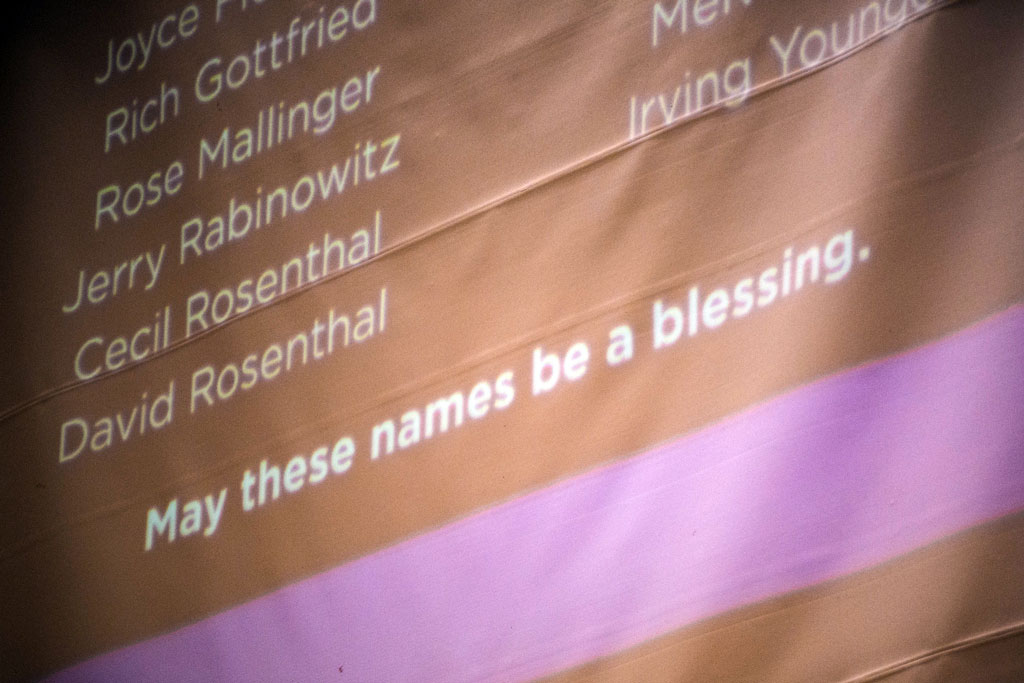

Three hundred and four miles away, David Rosenthal, fifty-four, walks through the doors of the Tree of Life Synagogue just as he’s done every other Saturday for decades. Positioning himself inside the sanctuary, he busies himself arranging prayer books and shawls for services. His older brother, Cecil, stands at the back of the sanctuary, greeting congregants. Like many who are intellectually disabled, these brothers appreciate the predictability of a Shabbat service with its routines and rituals.

◊

October 27, 2018 9:42 a.m., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Matthew spins in circles, stomps his feet, and shrieks with delight, doing what his mother calls his “happy dance” as she makes his smoothie—frozen pineapple, banana, and mango. He has already asked his mother to tell him the “story of my day” many times this morning, fisting his right hand in a ball while leaving his left hand open and moving them in sync as if he is opening a story book. “You’re going to have a smoothie,” his mother says. “We are going to go for a walk; we will come home and eat lunch, and then you will play with your puzzles and books.”

Had his mother been shown a picture of David and Cecil Rosenthal, she would have taken note of David’s shirt, untucked from the front of his pants, and the way his eyes squint more than the average person when he smiles, as if he is using every available facial muscle to feel happiness.

Their graying hair would make her uneasy. She can’t bear to think of a time when her son will be middle-aged himself, and she too old to care for him.

As she pours Matthew’s smoothie into a glass, she remembers her dream from last night, a recurring dream in which she and Matthew are having a “normal” conversation, although all he is capable of in “real life” are approximations of words that only she and those who know him well can understand. Their conversations in these dreams are lovely, but she never remembers what they were about. Some nights she tries to force the dream, promising herself that this time she will remember the words. But it never works. She doesn’t have that kind of control.

◊

9:54 a.m., Squirrel Hill, Pennsylvania

In the neighborhood surrounding the Synagogue, people begin their Saturday morning routines. Some wearing raincoats will walk their dogs as a light mist descends. Others will anticipate the afternoon Pitt football game or prepare lists for their Saturday food shopping.

From the parking lot of the Giant Eagle grocery store, shoppers hear a booming racket piercing the stillness of the morning. What construction is so important that such loud equipment must be used this time of day? they might ask. The popping explosions become sickeningly regular and staccato. Some who know what gunfire sounds like keep track of bursts.

The first 911 call comes into dispatch. “We are being attacked,” the caller whispers.

“Get out of there and don’t let anyone else in,” the operator responds.

◊

9:57 a.m., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Matthew’s mother flips on the radio as she puts lemon poppy seed muffins into the toaster oven. The announcer reports about a shooting spree in a synagogue in a quiet neighborhood in Pittsburgh, a neighborhood she might be surprised to know is strikingly similar to her own, with brick and stone homes constructed at the turn of the century, gracing the community like sleepy unassuming giants.

Rinsing blueberries at the sink, she raises her head and stares through the window into the half-eaten eyes of a Jack-o-Lantern. Halloween is four days away. For the first time she notices the jagged bite marks scarring its face. The squirrels seem more aggressive and hungrier than usual this season, as if they and their food source are not in alignment. She remembers a film she saw some thirty years ago called Koyaanisqatsi, a Hopi word meaning “life out of balance.” Instead of humanity growing apart from nature, as it did in the film, here in her backyard nature was growing apart from itself. She can feel herself shaping the natural world to the growing unease inside of her.

She turns on the blender, drowning out the radio. The noise is jarring, but she welcomes a reprieve from the relentless news coverage. She can’t bear to think how she might protect her son from gunfire if they were out in the world together. He wouldn’t understand. If anything, he’d be attracted to the overwhelming sensory sensation of repetitive bursts crackling through his body.

She wishes she could talk to him about the shootings, try to make sense of the insanity. Twenty-one years of living with him doesn’t erase this desire in her. If anything, it grows stronger.

Matthew spins in circles again, this time his arms outstretched like wings, bumping into her every so often. He’s laughing too, because for him there’s nothing better than the anticipation of a smoothie and muffin for breakfast on Saturday with his “Mama.” She notices that the front of his shirt has come untucked.

◊

9:59 a.m., Squirrel Hill, Pennsylvania

Bernice and Sylvan Simon, eighty-four and eighty-six respectively, sit side by side in the pews as they anticipate singing the Sh’ma, an ancient prayer that opens Saturday morning services. Sylvan’s face is all curves: the rounded chin, the bulbous nose, the arches on either side of his mouth. He has the face of a kindly neighbor who picks up windblown trash from neighbors’ lawns. Bernice delighted in singing “You Are My Sunshine“ to her kids when they were young. Hard of hearing, Bernice and Sylvan don’t take in the commotion in the hallway. They don’t see the gunman who bursts through the door of the sanctuary until he is directly in front of them and shooting. They die in the same synagogue where they wed sixty-two years ago.

Zone 5 Police Commander Jason Lando shouts into his radio, “Every available unit in the city needs to get here now.” Sirens flood the neighborhood. They whip down alleyways and ricochet off glass. Melvin Wax, eighty-seven years old, hears them as he hides in a storage room at the back of the chapel. People shopping in the nearby supermarket hear them.

◊

10:00 a.m., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Matthew’s mother would ordinarily delight in the sound of her son singing his favorite song “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” He sings like this: “Naah na nana na naaaaahna, na nana nana naaaaaaah…”

Part of her wants to join in but she can’t. She can’t muster the cheerfulness the song requires. Not when there’s been another mass shooting. Matthew lifts his eyes from the muffin crumbs he is rearranging on his plate and looks expectantly at her. He doesn’t realize she is just now remembering the words, but not the melody, to a chant she hasn’t sung in forty-five years. Sh’ma Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Echad. When she went to synagogue as a child, the congregation recited the Sh’ma at the beginning and ending of every service. She wonders as she says the words out loud if Matthew realizes they are in a different language.

◊

10:00 a.m., Squirrel Hill, Pennsylvania

Rose Mallinger, ninety-seven, slowly bleeds to death on the sanctuary floor. She is one of those women who grow more beautiful in old age. In photographs the lines on her face, especially those framing her eyes and mouth, suggest a life gently lived, despite the fact that she survived the Holocaust. Her daughter Andrea Wedner, sixty-one, accompanies her to services, as she usually does each week. Though she is shot too, she will survive.

Police stationed around the perimeter of the synagogue hear Commander Lando’s voice crackle through their walkie-talkies: “We are pinned down by gunfire. The shooter is firing out the front door of the building with an automatic weapon.”

A cold drizzle falls. Shards of glass litter the sidewalk.

◊

10:17 a.m., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Matthew’s mother thinks every Synagogue she has ever been in smells the same—a mixture of old carpet, musty prayer books, Aqua Net hairspray, coats reeking of moth balls, and the breath of old men.

◊

10:36 a.m., Squirrel Hill, Pennsylvania

Outside the sanctuary, a toppled bottle of whiskey sits on a white tablecloth, awaiting a baby naming ceremony, the whiskey steadily seeping into the carpet. A SWAT operator reports finding four bodies in the atrium.

Black polyester yarmulkes in a carved wooden receptacle nestle into one another. Men’s hats, some with feathers, still damp from the outside, rest on top of the coat rack. The eternal light suspended in front of the ark and a symbol of God’s presence, glows.

From certain angles the Tree of Life Synagogue could be mistaken for a nondescript government building. With its simple rectangular shape and cement walls, it fails to distinguish itself. But inside the sanctuary, soaring stained glass windows spread prisms of light across the pews.

Melvin Wax weeps in the darkened space where he hides. As the door swings open, he lets out a whimper and the gunman fires at him, knocking his body back onto the storage room floor. Fellow congregant Barry Werber, also hidden in the storage room, checks Melvin’s pulse. There isn’t one. The stained-glass windows remain intact.

◊

10:42 a.m., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

A glass hummingbird ornament above the kitchen sink reflects blue and green light onto the counter. A siren wails in the distance and for a minute Matthew’s mother assumes it is responding to the killings. She feels protected in her kitchen, her son within sight of her in the next room. She tells herself not to go outside where they might be vulnerable. Then she remembers that they live in a different city six hours away. The tooth she had a root canal on ten years ago throbs.

Matthew gets up from the living floor where he is assembling puzzles and makes signs for “siren.” He rotates his fist in the air over and over again until his mother says, “Yes, I hear the siren.”

◊

10:54 a.m., Squirrel Hill, Pennsylvania

Joyce Fineberg, seventy-five, who prayed at the Tree of Life synagogue every day since her husband’s death, lies dying. A retired researcher from nearby University of Pittsburgh, she had recently joined the Board of the Synagogue to help revitalize the congregation. Her bangs and chin length hair give her a no-nonsense appearance.

Daniel Stein, seventy-one who has recently become a grandfather lies dying as well. His children often joked that he hadn’t bought a new tie in years—that he didn’t care about style. Richard Gottfried, sixty-five, a dentist who treated uninsured refugees and immigrants, lies dying too.

What are the last sounds they hear? Bullets bouncing off walls or hitting flesh? People moaning? Or maybe something more consoling like soft water droplets hitting the stained-glass windows, or starlings chirping in a nearby tree, or even retreating footsteps muffled by carpeting, a door opening, then closing, indicating an end to the mayhem.

◊

11:02 a.m., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Matthew listens for the sound of crunching leaves as he tramples through the neighborhood on his Saturday morning walk with his mother. Unlike Pittsburgh, the day in Philadelphia is dry. Yellow leaves on oak trees blaze like flames against a gray sky. Acorns ping as they drop onto parked cars.

In preparation for Halloween, the Malinowskis decorated their windows with bloody handprints. The Sussons have strewn yellow police tape across their front door. The Agnettas staked a skeleton hand in the ground, and it reaches up, as if it were attached to somebody buried alive.

Matthew crouches down on his hands and knees to get a closer look at a giant black spider decoration on the James’ fence. Afraid to touch it, he places his mother’s hand on it to see if it moves.

◊

11:08 a.m., Squirrel Hill, Pennsylvania

Injured and bleeding, the shooter finally follows police orders. He crawls on the floor and surrenders his guns. He’s taken into custody.

◊

11:21 a.m., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Matthew and his mother return home from their walk. He takes up his picture books again, this time lining them in a straight row on the floor.

The melody of the Sh’ma, deeply submerged all morning, unaccountably surfaces and his mother, sitting on the sofa, begins to sing. Matthew stops and listens, perhaps because this melody is unlike all the others in her repertoire with its minor key and melancholy. Then he hums with her, and for a passing moment the tiny muscles around his eyes and his forehead strain. She wonders if he experiences the sense of yearning in the music that she does.

On another day she might have sung “You Are my Sunshine.” But today she wants to be true to her emotions, wants Matthew to somehow understand her grief and know that something is different. Feeling restless, she goes to the windows and opens the Venetian blinds. Shards of light refract on the wooden floor like pieces of broken glass. Matthew touches them as if they possess some kind of life force. In a minute the sun will shift in the sky and they will be gone. But for now, she and Matthew focus on the same experience, which is what she realizes she’s been hoping for all morning.

◊◊

Debra Fox’s stories and poems have appeared in bioStories, Embodied Effigies, Hyperlexia Journal, Blue Lyra Review, Heron’s Nest, Haiku Canada Review, Modern Haiku, and Frogpond. She is an attorney and founder of Story Tributes, an enterprise that preserves the stories of people’s lives. She lives on the outskirts of Philadelphia with her family.

Debra Fox’s stories and poems have appeared in bioStories, Embodied Effigies, Hyperlexia Journal, Blue Lyra Review, Heron’s Nest, Haiku Canada Review, Modern Haiku, and Frogpond. She is an attorney and founder of Story Tributes, an enterprise that preserves the stories of people’s lives. She lives on the outskirts of Philadelphia with her family.

Image credit: Governor Tom Wolf on Flickr

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Issue #27.