Becky Tuch

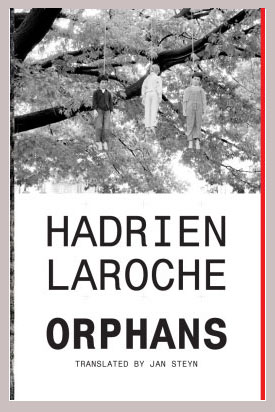

ORPHANS

Four in the morning and Maddie and I have nowhere to go. I said I was sleeping at her place and she said she was sleeping at my place and, well, now we’re in this diner. We’re both afraid to go home, me not wanting to wake my mom whose voice can be as shrill as hard rain and Maddie not wanting to bother her own parents, who’ve been having a hard time ever since her one brother ran off with the Krishnas and her other brother started rescuing stray dogs.

Hours back, we’d put on our platform shoes, took the F train to the city and stood in line for a rave. When the bouncer looked at my ID, which said I was sixteen, he turned us away, saying you had to be eighteen to get inside. Maddie protested, said of course we were eighteen, sir, there’s just a mistake. But he just looked us up and down with our round baby faces and our eyes that were hungry for something but too young to know what. He turned to the line, said, “Next, come on,” and we were shoved off to the side into the hot open night.

On the subway back Maddie asked me who the hell gets a fake ID that says you’re sixteen. I shrugged, not knowing what to say, except that sixteen sounded pretty old to me.

“So one time,” I begin, and Maddie’s blinking her eyes so slowly, eyes big and brown the color of horse hair, freckles clustered all over her nose. She’s looking at me, waiting.

“One time,” I say, holding down laughter in my throat. “My brother…he came home with this girl and my mom…”

But I can’t finish the story. That’s how it is with Maddie. Trying to get the sentence out is like trying to stand on the foam in the ocean. I want to do something straight and clear, but all I can do is tumble and laugh and give in.

She shakes her finger. “Let me tell you about my brother.” She tells me about the older brother who went to California to follow the Dead and came back home in a Lightning Van, which was just a van with lightning bolts painted over it. Then about the other brother, who owns a pit bull and always wears reflective sunglasses.

“Will that be all for you ladies?” the waitress asks.

“We have nowhere to go!” we tell her.

“Poor things,” she says, and drops off the check.

Tonight, we are refugees. We are orphans. We are stars sprung loose from the solar system, clinging only to each other in our hot glowing orbit.

We can’t let each other fall asleep. Then they’ll kick us out for sure.

There are plenty of stories to tell, though. Stories about our brothers, both older, both lost to us in the dark forest of late adolescence. Stories about our parents, dim suns hovering. Fantasies that are dreams that live all day long in our minds and which we’ve never revealed to anyone, until now.

“I’m afraid of heights,” Maddie says.

“I’m afraid of getting fat,” I tell her.

“I’m scared I have an addictive personality. Both my brothers are addicted to drugs.”

“I’m scared I’ll never fall in love. Both my parents are dying from loneliness.”

Just around the time the sun is coming up, the bell over the door jingles. The guys who come in are guys that we know, from back in the day when we used to hang around in the neighborhood. JayJay is a skinny Puerto Rican boy with a sharp pointed Adam’s apple and a smooth face the color of the coffee in our cups and always too much cologne and a way of looking at you that can make your thighs become butter.

Azzo is his friend, a taller, rounder, Puerto Rican kid with a soft voice and curly hair and gentle hands and the kind of guy you want to confide in and get advice from, usually advice that has to do with whether JayJay likes you. Azzo is sweet and tall and broad-shouldered and wears knitted sweaters in the wintertime and has a habit of putting his arms around girls in a protective loving way and has lots of acne.

They’re so high. That’s what we say the moment they sit down. “You are so high.”

They just laugh. Their hair and clothes smell like they’ve been rolling around in a marijuana field, and their eyes are screaming-red.

JayJay reaches across the table to pick up a menu and starts reading it, tapping his knuckles on the table. Azzo asks what we’re doing here.

“Just hanging,” we tell him, like it’s every night we stay up ‘til sunrise in the Grecian Corner diner.

“I’m hungry!” JayJay announces, his eyes big as he looks back and forth at me and Maddie, shrinking in our red leather seats, not sure which one of us he wants to eat first.

We talk about our respective nights, me and Maddie waiting on line at Nassau, being turned away in spite of our heroic feat of getting fake IDs made on West Fourth Street, then all our efforts to purse our red lips in a way that makes our cheekbones higher, our baby fat melt away.

They tell us about some party over at Luc Bustomanta’s house, how the music was bad but the weed was good, how the beer was bad but the dancing was good, how the party overall was bad but the walk there and back through the hot summer night was good and, now, since they’ve run into us, just getting better.

We don’t know what to say. How do we talk to these men, these boys with their soft hands and their red eyes and their loud pleased laughter? We want to run. We want to stay. We want to drink our coffee and be quiet and pretend they never came in and that it’s just me and Maddie and we are innocent as babies. We want to seduce them and dance with them and be the ones to make their nights ones that they will never forget.

JayJay eats a plate of waffles with whipped cream. Azzo eats oatmeal with sugar and fruit and nuts.

“Oatmeal?” JayJay says.

“I’m on a diet,” Azzo admits.

“Hey,” JayJay says. “You girls want to come back to my house?”

And what could be more perfect? We, who have been orphaned by our own incompetent plans. We, who are surely older than we are, who want nothing more from our lives than to grow out of them.

“Where do you live?” I say, but by then we’re already out on the avenue and stepping into the warm summer night.

JayJay leads us into his bedroom and doesn’t turn the light on. He’s got a bunk bed with two thin mattresses. Up on the top bunk there’s a white window curtain and if you peek through it you can see the street that leads up to the schoolyard where we all used to hang out and play handball and drink forties, before Maddie got into raves and I got into following Maddie wherever she went.

For a long time, we do nothing but sleep, the four of us like sardines lying side by side, warm and snug and safe in the darkness of the room and the night.

The first thing that wakes me is the tingling in my shins. When I open my eyes, JayJay is on top of me, his left hand around my ribs, slowly sliding upward, his right hand pressing down on my hip, pushing into the mattress. His lips are on my throat; his hair smells of coconut oil. Then his forehead is on my chin, a firm pressure. His tongue tastes of sleep, of whipped cream, of maple syrup.

I can feel his legs moving between my legs, like eels squirming up along the shore. And my eyes are flickering and I’m running my hands along his back, up and down, soothing, whispering, “Don’t stop, don’t stop.”

On the mattress below me I can hear Azzo and Maddie doing the same thing. The same swishing of the sheet. The same creaking of the mattress. The same sticky sounds of lips and saliva, boy grunts and girl hums and bodies entering bodies, skin yoking itself to skin. The same darkness wrapping itself around us like the arms of our parents, holding us safely and tenderly in the night.

Eventually, we drift back asleep and I wake to find Maddie up in the bed beside me, curled up like a baby lamb. I turn to her, caress her back, run my hands down her hair.

The boys are out of the room and daylight is spilling in. Blue and bright through the thin white window curtain. I hold Maddie like she’s my child. I kiss the top of her head like my mother always would to me and my brother.

“Are you sleepy?” I say, lips near her skull.

She nods against me.

“Me too,” I say.

“Do you think it’s too early to go back home?”

“I think it’s okay now.”

We dress and make our way into the hallway. JayJay and Azzo are in the living room talking to JayJay’s aunt. She’s got a cane stretched out before her and one leg bent, the other straight in front of her. She tells us to sit. We do. Her voice is raspy like a thousand cigarettes have been smoked and burned inside her lungs.

“Why are you dressed like that?” She points her cane to our platform shoes, our pants.

“We were going to a rave.” Maddie’s voice is soft, apologetic almost.

JayJay’s aunt bangs her cane on the floor. “You look horrible,” she says. “Ridiculous.”

Maddie and I look at each other. JayJay and Azzo look at us. We all look at the floor.

“I’m a lesbian,” says JayJay’s aunt. “And I sure wouldn’t fuck ya.”

“Well,” Maddie says. “Okay then.”

She bangs her cane on the wooden floor, many times, over and over. “Ya hear me?” She points her cane at Maddie as she lets out a loud raspy laugh. “I say, I’m a LESBIAN. And I WOULD NEVER FUCK YOU.”

I stare at Maddie, wondering what she’s thinking, what she’s going to do.

But all she says is, “I hear you,” and it’s the way she looks away from me then that tells me how alone we are, how adrift. We miss our older brothers. We miss being small. We miss believing that there is such a thing as a grown-up, and that grown-ups live on a place called land. ‘Cuz if there are no grown-ups, and there is no land, where do you return home to?

After a moment, Maddie and I push each other up, leaning against our armrests. We think it’s time to go. We stand and walk through the hallway, JayJay trailing behind us. At the door he kisses me on the lips, reaches for my waist. Then he leans over, kisses Maddie on her lips, cupping the back of her head.

“Fun running into you girls.” He smiles a sweet boyish smile.

“You too,” I say.

“We’ll have to do this again sometime,” Maddie says.

And then she and I walk, arm in arm, shoulder to shoulder, heads pressed close, down the front steps of JayJay’s house and slowly along the sidewalk, down toward the avenue, where, just over the lips of the buildings, on top of the houses and bridges and stores, the radiant round sun is beginning to rise. It’s a Sunday. The day is just beginning.

Becky Tuch is the founding editor of The Review Review, a website dedicated to reviews of literary magazines. She has received literature fellowships from The MacDowell Colony and The Somerville Arts Council and her fiction has won awards from Moment Magazine, Glimmer Train, Briar Cliff Review, Byline Magazine and elsewhere. Other writing has appeared in Salon, Virginia Quarterly Review online, Hobart, Quarter After Eight and other print and online publications. Find her at www.BeckyTuch.com.

Becky Tuch is the founding editor of The Review Review, a website dedicated to reviews of literary magazines. She has received literature fellowships from The MacDowell Colony and The Somerville Arts Council and her fiction has won awards from Moment Magazine, Glimmer Train, Briar Cliff Review, Byline Magazine and elsewhere. Other writing has appeared in Salon, Virginia Quarterly Review online, Hobart, Quarter After Eight and other print and online publications. Find her at www.BeckyTuch.com.

Image credit: Nika Gedevanishvili on Flickr

Read more from Cleaver Magazine’s Issue #8.

ORPHANS

ORPHANS