Cleaver Poetry Reviews Editor Carlo Matos has published seven books, including It’s Best Not to Interrupt Her Experiments (Negative Capability Press). His poems, stories, and essays have appeared in such journals as Iowa Review, Boston Review, and Rhino, among many others. Carlo has received grants from the Illinois Arts Council, the Fundação Luso-Americana, and the Sundress Academy for the Arts. He is also a winner of the Heartland Poetry Prize from New American Press. He currently lives in Chicago, IL and is a professor at the City Colleges of Chicago. He blogs at carlomatos.blogspot.com. Contact him by email.

Cleaver Poetry Reviews Editor Carlo Matos has published seven books, including It’s Best Not to Interrupt Her Experiments (Negative Capability Press). His poems, stories, and essays have appeared in such journals as Iowa Review, Boston Review, and Rhino, among many others. Carlo has received grants from the Illinois Arts Council, the Fundação Luso-Americana, and the Sundress Academy for the Arts. He is also a winner of the Heartland Poetry Prize from New American Press. He currently lives in Chicago, IL and is a professor at the City Colleges of Chicago. He blogs at carlomatos.blogspot.com. Contact him by email.

IN LIEU OF FLOWERS, poems by Rachel Slotnick, reviewed by Carlo Matos

IN LIEU OF FLOWERS by Rachel Slotnick Tortoise Books, 48 pages reviewed by Carlo Matos Rachel Slotnick’s debut collection, In Lieu of Flowers—an eclectic combination of lyric poems, flash prose, and mixed-media paintings by the author, who is also an accomplished painter and muralist—is part in memoriam and part Ovid’s Metamorphosis. The paintings are of particular interest because they play an essential role in how we understand the poems rather than being simply decorative or extraneous as can sometimes happen when paintings and poems are paired up together in such a context. Most are essentially portraits, though not purely mimetic ones. Her paintings have a surreal quality, the edges often blurred as one image becomes another: a beard becomes a fish, a shirt melts into the coral of the sea floor, and flowers, always flowers sprouting where they desire. “I tried to paint my grandfather,” says the speaker, “and the figure devolved into flowers.” Often the paintings also include multiple perspectives of the same central figure, reminding me conceptually more of cubism than surrealism, Picasso’s figures (of Françoise Gilot, for example) often turning into flowers as well. Althought Slotnick’s paintings and poems were conceived separately, it is clear that what motivated the ...

BEAUTIFUL IN ITS SLOWNESS: An Interview with Rachel Slotnick by Millicent Borges Accardi

An Interview by Millicent Borges Accardi, edited by Carlo Matos

BEAUTIFUL IN ITS SLOWNESS: AN INTERVIEW WITH RACHEL SLOTNICK Originally from Los Altos, California, author, muralist and hybrid artist Rachel Slotnick has work in the permanent display at the Joan Flasch Artist Book Collection at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Recently, she has completed murals for the 35th, 39th, 46th, and 47th wards in the Windy City. Slotnick currently is full-time faculty at the City Colleges of Chicago and an adjunct at the Illinois Art Institute and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her literary publications include Mad Hatter’s Review, Thrice Fiction, and The Brooklyn Rail, among others. Slotnick was the winner of Rhino Poetry’s Founder’s Prize. Her debut book of poetry/art entitled, In Lieu of Flowers is available from Tortoise Books. To view the full scope of her work, both visual and literary, check out her webpage: rachelslotnick.com. Millicent Borges Accardi: How did you decide to combine artwork and poetry? Which came first? I mean did you have the illustrations and write ekphrastic poems about the art or did you write the poems and select art to accompany the written words? Rachel Slotnick: Everyone kept telling me ...

BEAUTIFUL IN ITS SLOWNESS: AN INTERVIEW WITH RACHEL SLOTNICK Originally from Los Altos, California, author, muralist and hybrid artist Rachel Slotnick has work in the permanent display at the Joan Flasch Artist Book Collection at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Recently, she has completed murals for the 35th, 39th, 46th, and 47th wards in the Windy City. Slotnick currently is full-time faculty at the City Colleges of Chicago and an adjunct at the Illinois Art Institute and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her literary publications include Mad Hatter’s Review, Thrice Fiction, and The Brooklyn Rail, among others. Slotnick was the winner of Rhino Poetry’s Founder’s Prize. Her debut book of poetry/art entitled, In Lieu of Flowers is available from Tortoise Books. To view the full scope of her work, both visual and literary, check out her webpage: rachelslotnick.com. Millicent Borges Accardi: How did you decide to combine artwork and poetry? Which came first? I mean did you have the illustrations and write ekphrastic poems about the art or did you write the poems and select art to accompany the written words? Rachel Slotnick: Everyone kept telling me ...

HOW TO BE ANOTHER by Susan Lewis reviewed by Carlo Matos

HOW TO BE ANOTHER by Susan Lewis Červená Barva Press, 81 pages reviewed by Carlo Matos In How to be Another, Susan Lewis explores the full range of the prose poem form. These poems read like short speculative essays in the tradition of Montaigne, which is to say they have a metaphysical or epistemological bent to them. “Most knowing goes unlicensed,” says the speaker archly in “Introduction to Appreciation.” We are not dealing in this book with the esoteric details of autobiography or memoir but with the broader experiences of humanity as a species. How to be Another isn’t concerned with the kind of surface empathy or watered-down existential day-seizing of self-help books (as the title might suggest) but is instead a work of anthropology—though, clearly, these perspectives must intersect to some extent. For example, the speaker of “Introduction to Narcissism (III)” says, the “point is, self-awareness confers little evolutionary advantage. We are not wired for objectivity.” However, later in the same poem, the speaker acknowledges that the “pain” caused by self-awareness “is relentless, staying with you longer than any friend or flattering memory.” The shift to the second-person pronoun is telling for although the “you” is largely rhetorical in ...

BANNED FOR LIFE by Arlene Ang reviewed by Carlo Matos

BANNED FOR LIFE by Arlene Ang Misty Publications, 81 pages reviewed by Carlo Matos Arlene Ang’s Banned for Life is obsessed with bodies, especially dead bodies. In fact, there is a reference to a corpse in nearly every poem in the first section and in many cases the corpses are literally present. And in the poems that do not have corpses, death is often not far or on hold. In “Mountains,” for example, the subject of the poem is referred to simply as “the body:” With both hands, the body touched itself where the physician lingered with the stethoscope . . . on that part where everything went wrong. The “body” of “Mountains” might be the mother figure of the next poem, “To Sweat,” who has cancer. In these poems Ang demonstrates how the ravaging power of a disease like cancer can trap us inside our own bodies or reduce our humanity to its component, material parts. In the third section of the book, when Ang returns once again to her bodies, she develops the notion of dismemberment overtly. In “Rediscovering Paris Through Female Body Parts,” a woman is carved-up like a city map. This part is the Seine, another ...

TWO FAINT LINES IN THE VIOLET by Lissa Kiernan reviewed by Carlo Matos

TWO FAINT LINES IN THE VIOLET by Lissa Kiernan Negative Capability Press, 112 pages reviewed by Carlo Matos Lissa Kiernan’s debut collection radiates, burns, and fluoresces like uranium glass, like a “bed of plutonium nightlights.” Many of the poems, especially in the first half of the book, focus on her father (“My father, my leather fetish, my motorcycle papa”) and deal largely with the grief she experiences as he dies from cancer. But these more intimate revelations are not allowed to remain solely in the realm of the personal, set off as they are by poems of a more political, or rather politically charged nature. These poems—some of which are found poems based on official documents and newspaper reports—indict the Yankee Rowe Nuclear Power Station for contaminating the town where her father lived in Massachusetts. The intrusion of the faceless other on the integrity of the human body—and the power plant is not the only example of this—gives these poems their unique and disturbing power. For example, in “The River, My Father,” the very first poem in the book, Kiernan appears to have written a prose poem, but although it is a solid block of text, it is made up almost ...

ZOONOSIS by Kelly Boyker reviewed by Carlo Matos

ZOONOSIS by Kelly Boyker Hyacinth Girl Press, 39 pages reviewed by Carlo Matos Kelly Boyker’s chapbook, Zoonosis, is loaded from cover-to-cover with fantastical creatures, folktale monsters, and twentieth-century “freaks” drawn from the pages of Robert Ripley’s “Believe It or Not.” The Ripley’s characters are of particular interest because they are often postmodern updates of the original chthonic creatures of Greek myth. There is a child Cyclops, for example, a tribe of crab people, and Orthus—the less-famous, two-headed brother of Cerberus. The modern-day Orthus is the result of a macabre experiment by Russian scientist, Vladimir Demikhov, who “successfully grafted the head of a puppy onto the body of a full grown Mastiff” (“Orthus”). Time and again, as this example makes clear, the true monsters of Boyker’s world turn out not to be the wolves or the so-called freaks, whom she often treats with compassion and understanding, but the “ordinary” people. Even when the wolf bites, she seems to be saying, it is only acting according to its nature. The humans, on the other hand, sit dreaming of cotton panties blowing on a clothesline . . . teeth jutted forward, all the better to eat them, all the children. (“American ...

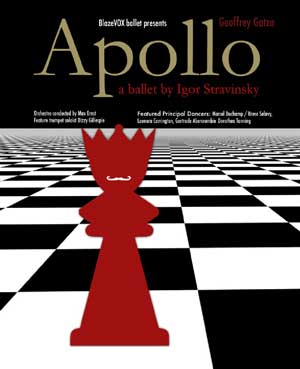

APOLLO by Geoffrey Gatza reviewed by Carlo Matos

APOLLO by Geoffrey Gatza BlazeVOX

, 168 pages reviewed by Carlo Matos Geoffrey Gatza’s Apollo is an all-out assault on the reader, like facing an opponent who senses you’re about to wilt and so presses the action. Every time we think we know what he’s doing, another surprise comes our way. And this is how good conceptual poetry should be—not just the simple execution of a clever conceit but a text that threatens at every turn to burst from the inside out and take the reader with it but never does. Taking the shape of a souvenir program for a one-night performance of Stravinsky’s ballet of the same name, the book contains a myriad of Dada-like exercises: poems generated by a John Cage-like method of assigning words to each square on a chess board and to each piece and then playing out the game between Marcel Duchamp and then US chess champion, Frank Marshall, at the Chess Olympiad in Hamburg in 1930 (accompanied by pictures of each position and a cat), an Arthurian legend based on the Lady of Shallot, a three-act play where Duchamp somehow manages to play himself as Rrose Sélavey (his female alter-ego), and a business letter to ...

HONEY by Carlo Matos

Carlo Matos

HONEY You could tell they weren’t from around here by the way they spread their honey, with a finger instead of a spoon—all thin, pilling at the rug of bread. It was like the day she finally admitted she had Hitler mannerisms: those arms, the contortions, the albedo—even the way the sweat flew off her cheeks—the fact that she always seemed to be yelling: her spit, an electron planning its next escape. Already there were so many things she couldn’t do—just to be on the safe side. She would never grow a mustache, for example, but, of course, now she really wanted one. She would never ride bikes under a blood sun elbowing down the horizon: a siphonophore with its chain of red bellies trawling the deepest sea. Luckily, although she had not always felt this way, adventure was no longer something you had to go out and find on tippy toes on the bikes the color of last year’s foams, which are now utterly forbidden; it’s something that grows on you—a wax tough on the teeth—a hive wall, a symbiote. There was so much dead telemetry while she waited for the off chance the waters would come and ...

HONEY You could tell they weren’t from around here by the way they spread their honey, with a finger instead of a spoon—all thin, pilling at the rug of bread. It was like the day she finally admitted she had Hitler mannerisms: those arms, the contortions, the albedo—even the way the sweat flew off her cheeks—the fact that she always seemed to be yelling: her spit, an electron planning its next escape. Already there were so many things she couldn’t do—just to be on the safe side. She would never grow a mustache, for example, but, of course, now she really wanted one. She would never ride bikes under a blood sun elbowing down the horizon: a siphonophore with its chain of red bellies trawling the deepest sea. Luckily, although she had not always felt this way, adventure was no longer something you had to go out and find on tippy toes on the bikes the color of last year’s foams, which are now utterly forbidden; it’s something that grows on you—a wax tough on the teeth—a hive wall, a symbiote. There was so much dead telemetry while she waited for the off chance the waters would come and ...